U of T professor’s book explores Toronto’s diversity through local public school

Published: April 19, 2017

The tiny archive room at Clinton Street Public School in downtown Toronto tells a fascinating story, not only about the 129-year-old primary school but also about the city’s journey to become the multicultural metropolis it is today.

Robert Vipond, a University of Toronto political science professor at the Faculty of Arts & Science and the interim director of the Centre for the Study of the United States at the Munk School of Global Affairs, tells the school’s story in his book, Making a Global City: How One Toronto School Embraced Diversity, published by University of Toronto Press.

Coming across the Clinton’s story was somewhat of a happy accident, says Vipond, whose daughter was a student at the school.

“Most of my academic career, I've worked on American-Canadian politics, especially constitutional politics so I touched briefly on education and immigration but had no deep or abiding interest in it,” he said.

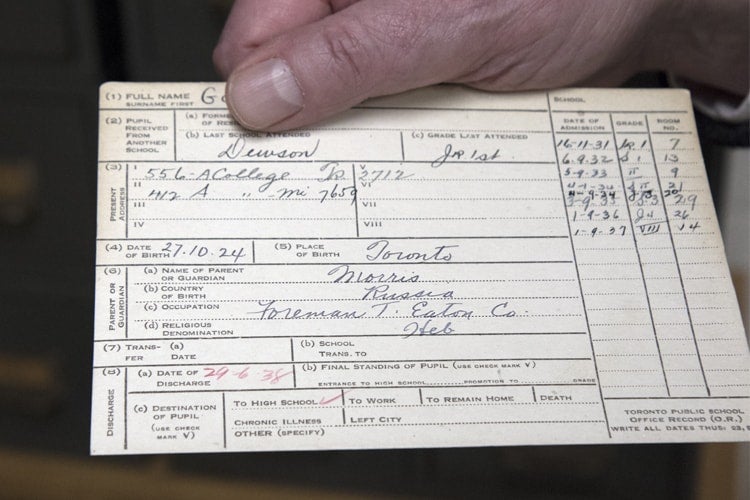

That was until he was told about the extensive catalogue of registration cards – from 1920 to the 1990s – housed in the school’s archive room. The cards provided details about the students and their families – including their ethnicities and parents’ professions – that painted a picture of the school’s population over time, mirroring larger immigration trends in the city.

“I began to realize a lot of the work I've done has centred on the ideas of citizenship and that's what came through in the book – these debates about citizenship changed over the course of the years but were really important for gateway schools, immigration and immigrant kids.”

Researchers sorted through thousands of registration cards like this one to learn more about the students who went to Clinton Street Public School (photo by Romi Levine)

Korryn Bodner worked as a researcher on the book while completing her master’s in political science at U of T. She analyzed the extensive data collected from the registration cards, identifying immigration patterns.

“Delving into the school, it really paints a picture of how diverse it was and is, and how much that's changed over the years,” says Bodner, who is currently working toward a PhD in ecology and evolutionary biology.

Bodner says she and a team of researchers were able to spot the exact moments when the school’s population shifted between different immigrant groups.

Through this research, Vipond identified three distinct periods in the school’s history: from the 1920s to 1950s, a large Jewish community came to the school, from the 1950s to the 1970s, it was students from Italy and Portugal, and from the 1970s onward, students came from all over the world.

“Each of those periods have a distinct approach to citizenship, and each of them had a signature issue that distinguished the school from other schools,” says Vipond.

A household science class at Clinton in the 1920s when the school had a large Jewish population (photo courtesy of University of Toronto Press / Clinton Street School Archives)

In the 1940s, for example, schools were required to provide religious Christian instruction to students, but with a large Jewish population, teachers decided to rebel, he says.

“What happened in that case was the teachers of Clinton took a pass – they showed a little bit of civil disobedience actually in just not complying with that law,” says Vipond.

In the 1950s, Clinton developed its own English as a Second Language (ESL) curriculum, long before it was formally a part of the Toronto public school system.

Of the 75 Clinton graduates, parents and administrators that Vipond interviewed, some memorable stories stuck with him.

A notable graduate was Richard Reed Parry, who went on to become a musician in Canadian super-group Arcade Fire. Parry attended Clinton in the 1980s where he was encouraged by one of his teachers to pursue music.

“Music at Clinton really changed his life and made him realize what a great medium it was, and that he could do it,” he says.

Vipond also recalls a teacher named Mr. Timpson who built a menorah from hula hoops so his Jewish students could celebrate Hanukkah at school.

Clinton Street Public School is located on Manning Avenue between College and Bloor streets (photo by Romi Levine)

While countries like the United States, the United Kingdom and even Canada are struggling with their cultural identity in a multicultural world, Clinton can be seen as a crucible for how diverse groups of people can find middle ground, says Vipond.

“The language around citizenship and multiculturalism has been degraded by being set into a polarized binary,” he says. “Either you're in favour of multiculturalism, or you're in favour of something like complete assimilation, or closing doors to immigrants all together.”

“I'm reminded of the old joke, ‘Why did the Canadian cross the street?’ The answer is ‘to get to the middle.’ I think that actually describes the Clinton approach to diversity.”