U of T researcher studies how movies shaped the public's understanding of investigative journalism

Published: December 11, 2019

In one of the most iconic scenes in All the President’s Men, a mysterious figure emerges from the shadows of a deserted parking garage and tells Bob Woodward, a young, hungry reporter, “Just follow the money.”

The classic 1976 movie established several elements that came to characterize movies about investigative journalism – not to mention the occupation itself, according to a new study by Sandford Borins, a professor in the department of management at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

“The average person doesn’t know much about journalism at work, because they rarely come into contact with journalists. They only see the output,” Borins says.

“Movies about investigative journalism are the primary way that the public learns about what investigative journalists do.”

Borins analyzed six American movies about investigative journalism made in the United States over the last 40 years, beginning with All the President’s Men, which follows reporters Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) as they expose the Watergate scandal.

Movies in the same genre often incorporate the same fables – structural elements such as character types, themes and plot points. Borins’s study, co-authored with scholar and author Beth Herst and published in Journalism Practice, looks at what fables exist in the subgenre of investigative journalism movies.

To define the fable, Borins used a unique methodology in which he identified 14 core elements of the investigative journalism fable and dubbed it the “heroic investigative journalism fable.” He discovered that James Hamilton, an economist at Stanford University, had studied applicants for the Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism and found a similar pattern.

In the heroic investigative fable, a team of journalists begin to research and then enlist support from their editor to pursue a story. The journalists interview sources and sift through mountains of documents, piecing the paper trail together. Despite opposition, the story is eventually published, leading to social change.

A unique element of the fable, and of the subgenre of investigative journalism movies, is the lack of screen time given to the journalists’ personal lives.

“In typical journalism movies, there’s always the love story in the back, and these movies purposely say, ‘That’s not what we’re talking about,’” Borins says. “I think that communicates to the audience a level of seriousness, that this is really important and it demands our complete attention.”

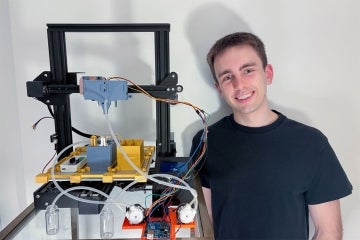

Sandford Borins, a professor of management at U of T Scarborough, says movies about investigative journalism can create unrealistic expectations at a time when reporters face allegations of “fake news” and mass closures of newspapers (photo by Ken Jones)

Borins then used the fable to examine five movies. Two were stories of clear success that embodied the heroic investigative fable (All the President’s Men and Spotlight). Two were stories in which the impact of the investigative journalism was lessened by conflicts with corporate managers of media outlets (Good Night and Good Luck and The Insider). The final two were counter-fables in which the investigative journalists ultimately failed (Truth and Kill the Messenger).

Borins says these movies can create unrealistic expectations of investigative journalism. In the real world, editors may decide an investigative journalist’s work is too risky to publish, thus, the story never makes it to film. People may also confuse it with breaking news reporting, meaning “audiences might come to the erroneous conclusion that investigative journalism is typical.”

“Hollywood always has a tendency to hype its heroes,” Borins says. “While there are occasional movies about failed investigative journalism, such as Kill the Messenger and Truth, the movies about successful investigative journalism have been more successful.”

The study, supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, cites several works on the impact of movies. These narratives can shape a person’s beliefs, their social and policy views, their activities in the public sphere and even inspire activism.

Borins notes that narratives in these movies can change the way people view investigative journalism and its role in a democratic society. He says understanding investigative journalism is increasingly important, particularly in the U.S. where journalists now face allegations of “fake news” and mass closures of newspapers.

Borins, for his part, remains hopeful.

“The fact that you have an administration led by someone for whom lying is like breathing and enablers who try to cover this up has stimulated investigative journalism at the national level in the U.S.,” Borins says.

“And journalists in different countries are aware of each other’s efforts.”