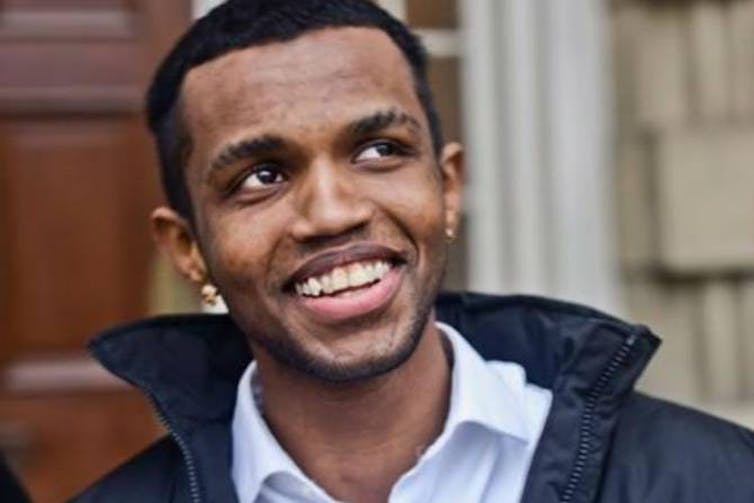

Why try to deport a man in Canada since childhood? U of T expert looks at the case of Abdoul Abdi

Published: March 14, 2018

Abdoul Kadir Abdi is facing deportation from Canada to Somalia.

As migration scholars and detention experts, we will show that while perhaps lawful, this deportation is the accumulation of governmental historical, social and moral failures. Abdi arrived in Canada as a six-year-old child, and is a product of this country. His deportation should be halted.

Abdi was born in Saudi Arabia to a Somali mother, and spent four years in a Djibouti refugee camp. Eighteen years ago, he was only six years old when he claimed asylum in Nova Scotia. With his mother deceased, Abdi arrived in the care of his sister and aunts.

The province intervened to remove Abdi from his aunts’ care. The Nova Scotia Department of Community Services then placed him in foster care until he aged out of the system. Abdi was in 31 different “care” arrangements: permanent and temporary foster homes, halfway houses, hospitals, wards and so on.

Not one addressed his struggles, and some were abusive. The government did not apply for citizenship for Abdi despite pressure from the Abdi family.

When Abdi was about 18 years old, he was convicted on criminal charges. He served four-and-a-half years in prison and was released to a halfway house. It was at the gates of this house that the Canada Border Services Agency arrested him, took him to an immigration detention facility and began deportation proceedings to send him to Somalia.

Abdi has never lived in Somalia, a country under an extreme travel advisory alert.

Until they apply for and are granted citizenship, asylum-seekers are only granted permanent residence in Canada. Canadian law stipulates that asylum-seekers or permanent residents who receive criminal convictions carrying custodial sentences exceeding six months may be deported. Abdi’s conviction falls under this category.

This deportation order is wrong. With the support of his sister Fatuma Abdi, the Toronto chapter of Black Lives Matter has begun an anti-deportation campaign called All Out 4 Abdoul. His removal is being legally contested by his lawyer, Benjamin Perryman, with the support of the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto.

Through news conferences, social media and mainstream and prominent media coverage, Abdi and his supporters have called on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Ahmed Hussen, the minister of immigration, refugees and citizenship, to use their discretionary powers to stop the deportation. The Federal Court is now hearing the case.

Why has Abdi's plight struck such a visceral chord?

‘Scapegoats’ for poor policy

We argue that Abdi’s case illuminates how Canada is failing asylum-seekers, criminalized people and visible minorities. The federal government’s ongoing and persistent efforts to banish Abdi to Somalia indicate how asylum-seekers have once again become the scapegoats for poor policy.

We find local and federal government failures at various points culminating in this deportation order. On these grounds, we argue it’s the government’s responsibility to stop the deportation.

Firstly, Nova Scotia failed to provide Abdi’s aunts, themselves newcomers, with the full support they needed to raise the child and to keep him safe.

The decision to remove the child from his aunts contradicts the evidence that the best outcomes for children occur when they remain with their families. Nova Scotia is grappling with a disturbing history of abuses at the now-shuttered Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children in Dartmouth, where a provincial inquiry is entering its third phase. The decision to remove Abdi should be situated within a system plagued by institutional racism.

What’s more, as a Crown ward, the state shuttled Abdi among 31 different living arrangements in 12 years – on average, this is a new home every four-and-a-half months. Abdi has alleged that some of these homes were abusive.

Clearly, the state failed to provide him with sufficient care and support to assist him to make good life choices.

Crown wards at greater risk of committing crimes

Governments cannot control an individual’s actions, but we know that people from disadvantaged backgrounds commit crimes at a higher rate than the overall population. As a Crown ward, this child would have been at greater risk of offending. The community is right to expect that the support provided to Abdi should have been commensurate to the risk.

The Nova Scotia Department of Community Services also failed to execute its duty to assist Abdi in becoming a citizen. Given the logistical and other barriers hindering Crown wards from applying, this assistance was its policy-mandated responsibility.

Surely, it’s logical to have more long-term residents as citizens, and fewer people here as asylum-seekers, permanent residents, or other less-than-full statuses. At least 15 cases of former child refugees facing deportation are surfacing; of these, at least three have been deported to a country they have no connection to because of criminal activity after they turned 18.

Morality aside, this practice breaches international law: Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 7 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child state that everyone has the right to nationality and citizenship.

Finally, and most fundamentally, the government of Canada is failing to recognize that Abdi, who arrived in Canada as a six-year-old child, is the product of their state. Indeed it could be argued that, as a Crown ward, Abdi is even more a product of the Canadian system than others who were raised within a nuclear family unit.

By attempting to deport Abdi, the Canadian government has indicated an adherence to biological determinism: The view that Abdi's “nurture” – his social ties, relationships and mutually reinforcing personal and community histories – matters less than his “nature” as a perpetual foreigner.

The Somali Canadian community already faces significant challenges from “systematic, institutional racism on the part of schools, police and intelligence agencies and the media.” It would be a shame if the federal government fed in to false – not to mention racist – perceptions by continuing its efforts to deport Abdi.

Stephanie J Silverman is an adjunct professor of ethics, society and law at the University of Toronto. Amy Nethery is a senior lecturer in politics and policy studies at Deakin University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()