Study by U of T and Ryerson unpacks problems with Little Free Libraries

Published: May 4, 2017

Stuffed with old paperbacks, mini-free libraries dotting front lawns across Toronto are supposed to foster literacy, build community and improve access to books.

There’s just one problem. Researchers at U of T and Ryerson University say the phenomenon tends to be concentrated in well-educated, well-to-do neighbourhoods served by actual – and also free – public libraries, raising questions about whether they're actually encouraging others to read.

In a paper published recently in the Journal of Radical Librarianship, researchers say the take-a-book-leave-a-book boxes “are examples of performative community enhancement, driven more so by the desire to showcase one's passion for books and education than a genuine desire to help the community in a meaningful way.”

Little Free Library is a non-profit based in Wisconsin, which claims that it has 50,000 registered book exchanges worldwide and is “increasing book access and forging community connections.”

However, Jordan Hale, a geographer who is also a reference specialist at U of T Libraries, and Ryerson librarian Jane Schmidt are skeptical.

Listen to Schmidt discuss the study on CBC's As It Happens

Read more about the study in The Atlantic's City Lab

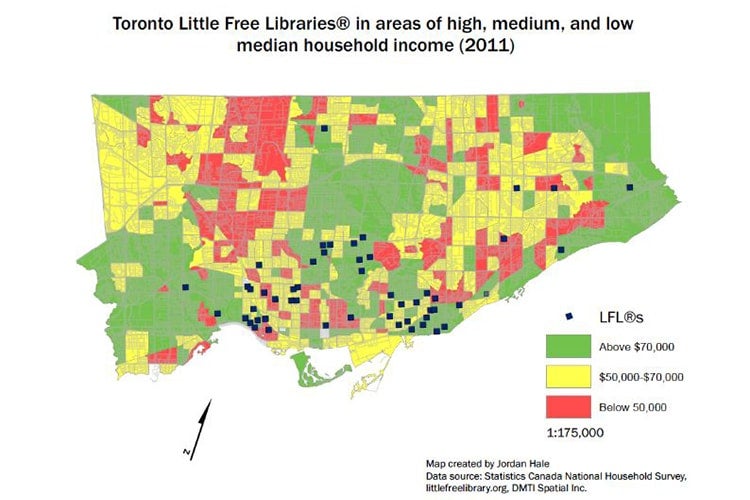

Using a spatial analysis of Little Free Libraries in Toronto and Calgary with data from Statistics Canada's 2011 National Household Survey, they show that the majority of the mini libraries in these cities are in wealthier, mostly white neighbourhoods where people are more likely to have university degrees – areas like the Beaches and Forest Hill.

Moreover, many of the libraries are near Toronto Public Library branches, the authors say.

“In other words, not in book deserts but in the neighbourhoods that already enjoy high access to books (as well as transportation and other public services),” they write.

Hale, who has a master's from U of T in cultural geography, says she became interested in investigating the Little Free Libraries after noticing that they are concentrated in a certain type of neighbourhood, she said.

She met Schmidt over Twitter, where they discussed pursuing a project on the Little Free Libraries.

“We have no problem with the concept of a neighbourhood book exchange or putting stuff out on the curb,” Hale told U of T News. “I just curb-scored a pair of red velvet pumps in my size as my neighbour was putting them out.

“We wanted to know what the organization was after in making this a brand, associating a cost with it and whether this was aiding their stated goals of improving literacy around the world.”

Jordan Hale is an original cataloguer and reference specialist in U of T's Map & Data Library (photo by Geoffrey Vendeville)

For their research, Schmidt registered and set up a Little Free Library herself, learning in the process that they aren't free. The registration fee ranges from $42.45 to $89 USD, according to the study, and the boxes go for between $179 and $1,254 USD.

The U of T and Ryerson researchers are also concerned that the Little Free Libraries may come to be seen as – in Hale's words – “alternatives to staffing and funding public library systems.”

They offer the story of Vinton, Texas as a “cautionary tale.”

In response to budget cuts, El Paso Public Library imposed a $50 fee on non-residents. The village of Vinton announced five new book exchanges to compensate, Hale and Schmidt say.

“This solution demonstrates that in at least one small corner of the world, politicians looked to this social enterprise as a solution to the lack of access to public library services,” they write.

Todd Bol, the founder and executive director of Little Free Libraries, says the researchers' “irritation is peculiar to me [him] because it really should be more about a celebration” of reading and community, but he added that he welcomes their suggestions for improvement. He told U of T News the Little Free Libraries aren't to be seen as alternatives to public libraries. “That's like saying a skateboard is as good as a sports car,” he said. “We know what we are – we're a box of books on a stick.”

If readers take anything away from their study, Hale hopes it will be that tackling the issues underlying inequality and access to books are complicated – and not easily solved by installing a box at the nearest street corner to offload books like Word 2003 For Dummies.

“They may look cute on the side of the road and on Instagram,” Hale said of the Little Free Libraries, “but we should look at how we can better support each other in these times of funding cuts [at libraries around the world].”

See the Toronto Star story