'Old-style gentleman' Douglas Joyce taught German at U of T for more than three decades

Published: November 13, 2018

Douglas Joyce was a modest and unassuming scholar who pursued his academic work quietly, while maintaining a deep and lifelong devotion to art, culture and music.

For more than three decades, he taught in the University of Toronto's department of Germanic languages and literature, and was head of German at Trinity College in the 1960s, before the department was united across the university in the 1970s.

Joyce, who retired in 1988, died in Toronto in July at the age of 95.

“He was an old-style gentleman,” says his former German department colleague Deirdre Vincent. “Douglas was uniformly and unmitigatedly courteous, considerate, reflective and gentle.”

Vincent says Joyce was unusual among academics because he was so quiet and self-effacing, and not driven by a desire for prodigious output. Indeed, while he wrote many papers, Joyce wrote only one book – a detailed scholarly analysis of the critical reaction, over 50 years, to one of the plays by Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

But he was highly productive in other ways, usually behind the scenes, says U of T Professor Emeritus Robert Farquharson, a longtime friend of Joyce who first met him at U of T in 1960. Joyce took on many administrative roles, and was one of the founders and the first secretary of the Canadian Association of University Teachers of German, which was created in 1961.

In 1965 Joyce and Farquharson started up the first Canadian journal of Germanic studies, called Seminar – a publication that still flourishes. “I became the first editor and he became the secretary and treasurer,” Farquharson says. “He was very conscientious and hard-working in that role. When we started the journal we were working on it alone.” That meant doing everything, including keeping track of subscribers, addressing envelopes and taking the journal to the post office.

Joyce spoke slowly because he thought things through very carefully before making a pronouncement, Farquharson says. “He was quiet, unassuming, but with a welcoming grin and a twinkle in his eye.” And he never seemed to lose his temper. “I don’t think I ever heard him raise his voice in anger, or even in annoyance. Probably the most strongly assertive sentence I heard from him was a gentle warning to a visitor: ‘I make a firm cup of tea.’”

Farquharson says Joyce was also popular with students. “He took a personal interest in them in a very gentle, patriarchal way.”

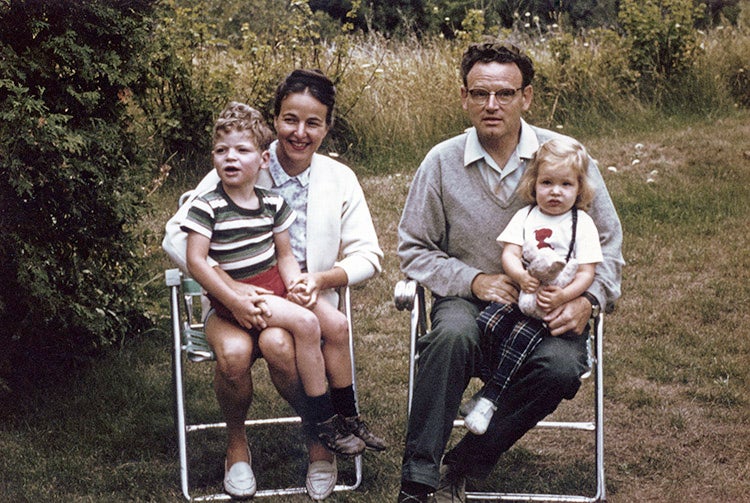

Douglas Joyce with his wife Dorothy and their two children (photo courtesy of the Joyce family)

Gerd Hauck, who came to Canada in 1979 from Germany to work as an exchange lecturer, met Joyce at U of T, where they became fast friends. Hauck, now a professor at Ryerson University, says he was able to slake some of Joyce’s keen curiosity about the political and social turmoil that was rocking Germany in the late 1970s and early 1980s. “He expressed a deep interest in how contemporary Germany was developing.”

While Joyce appeared on the surface to be reserved and quiet, he became much more warm and lively in social situations where he was comfortable, such as his own home or the home of friends, Hauck says. “With people he got to know, the reserve disappeared very quickly through a very subtle use of irony. He had the capacity to find humour in the small, in-between spaces. I could never detect a single fibre of negativity in him.”

Hauck helped proofread portions of Joyce’s book, which focused on von Hofmannsthal’s 1921 play titled The Difficult One. Joyce, Hauck says, was “the exact opposite of ‘the difficult one.’ He was an easy one, in the sense that he was easy to like, easy to get along with ... and easy to love because of the high ethical fibre in his character.”

Douglas Alick Joyce was born in St. John’s, N.L., the son of a minister at the Wesley United Church. His father, Rev. Joseph Joyce, established one of Newfoundland’s first radio stations, in order to ensure his parishioners in isolated communities, or who couldn’t make it to church, could hear the sermon and other uplifting material. But it was the German operas broadcast on the radio station that inspired his son and propelled him to his academic career.

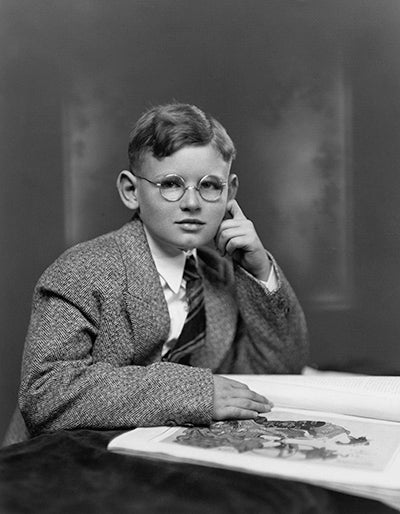

Joyce (pictured left as a child) pursued his studies of German at McGill University, then at Harvard University where he earned his PhD in German languages and literature.

Joyce (pictured left as a child) pursued his studies of German at McGill University, then at Harvard University where he earned his PhD in German languages and literature.

Joyce tried to enlist to fight in the Second World War, but he was turned away because he had had rheumatic fever as a child. Instead, his German skills were put to use censoring letters sent home by German prisoners of war housed in Canada.

After the war, Joyce spent time travelling and teaching in Europe, before joining U of T in 1950 as a professor of German language and literature at Trinity College. He became head of Trinity’s German department in 1960. Joyce's daughter Andrea says that her father loved the energy on campus and the conviviality of university life.

Joyce was deeply interested in the arts, and spent a lot of time attending theatre, opera and musical concerts. He was a photographer, painted watercolours, played the piano, and eventually took up clarinet as well. He shared a love of music with his wife Dorothy, who was a pianist and music teacher. “It felt like they were out practically every night at the symphony, chamber music, the opera or ballet,” Andrea says. “They embraced culture and art.”

Joyce was also devoted to travel. Several times he took the entire family to Europe for extended visits, spending part of the time on academic research. “Dad was never about short stays,” Andrea says. “He wanted to ensconce himself in a place.” Later in life he became fascinated with Egyptian history and culture, and took an extensive trip there with Dorothy in 2003.

After their son David was diagnosed with a learning disability, the couple became involved in improving education for children with the same issues. They were among the founders of what is now called the Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario. “Our house became a central place where people would meet. Kids would come, and they had young-adult groups meeting there,” Andrea says.

After years of a quiet retirement, in 2006 Dorothy was diagnosed with dementia, and she died in 2013. In his later years, Joyce moved into The Briton House retirement home in Toronto.

Andrea describes her father as “a very kind, gentle man. He wasn’t the centre of attention, but he had the best of intentions and was just a good human being.” He had a curious mind, a passion for learning, and lived a full, rich life, she says.

Joyce leaves his brother Carlton, his children David and Andrea, and grandchildren Kaleigh and Brigid.