Inside a humanitarian crisis: U of T medical resident treats Rohingya in Bangladesh

Published: October 30, 2017

Internal medicine resident Dr. Nabiha Islam just returned from Bangladesh, where she spent three weeks caring for Rohingya refugees in camps near Myanmar, also known as Burma. More than 600,000 Rohingya have crossed the border since August, fleeing extreme violence and persecution by the Myanmar military and civilians. The United Nations and leaders around the world have called the crisis ethnic cleansing.

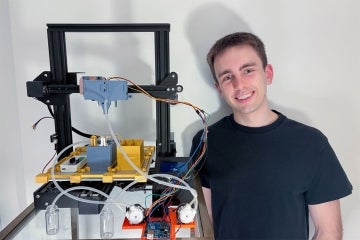

Islam (left with a refugee also named Nabiha) is a fourth-year resident who was on an international elective with the HOPE Foundation for Women and Children of Bangladesh. She spoke with writer Jim Oldfield about what she witnessed in the camps, how the crisis is unfolding and what the world can do to stop it.

Islam (left with a refugee also named Nabiha) is a fourth-year resident who was on an international elective with the HOPE Foundation for Women and Children of Bangladesh. She spoke with writer Jim Oldfield about what she witnessed in the camps, how the crisis is unfolding and what the world can do to stop it.

What conditions are the Rohingya facing in Myanmar and Bangladesh?

All Rohingya in Burma have suffered incredible oppression for decades and in many cases extreme violence. Most patients I spoke with had no health care and no access to education. They talked of how, if they could cobble together enough money to build a primary school, it would be burnt down by the Burmese military. If they had jobs, they were under the radar. Many have been essentially starved out of their own communities, their food markets closed down. Women seen with a niqab, hijab or burqa are beaten and their clothing torn off. In this most recent crackdown, there has been a concerted attempt to burn down villages with people inside them. If children tried to run, they were thrown into the fires of the burning homes. Women were corralled outside homes, stripped naked, and forced to watch while their husbands and sons’ throats were slit, then they were gang raped. I heard these stories repeatedly. And all this before they’ve even begun the journey to Bangladesh.

How far are they travelling to reach the border?

Most are fleeing hundreds of kilometres on foot. They have no food or water, in 35-degree Celsius heat punctuated by torrential rains. It’s the most difficult journey you could imagine. Oftentimes they speak of spending a week or more in the jungle, eating leaves. They have to cross rivers and marshes, and many have no ability to swim, so drowning is another danger for them in addition to the communicable diseases being spread along the way – infectious diarrhea, upper respiratory tract infections, fungal infections. Almost all are suffering from heat stroke and exhaustion.

What kind of help were you able to provide?

We lacked point-of-care diagnostic testing, that’s an area we could really work on. One NGO did have rapid antigen detection testing, and urine pregnancy tests were very helpful. But a lot of the care was on-the-spot diagnosis and treatment. If someone presented with shortness of breath and sharp chest pain, and had a fever and cough, we’d diagnose pneumonia and treat with antibiotics.

I spent the first week in Balukhali then moved to other camps, and they all had step-like formations carved into hills with the health camps at the base below. Some refugees were stuck high on the hills, so I started climbing. If someone was too sick to treat, there were tom-toms for emergency evacuation to a hospital. The Red Cross had set up a field hospital in one camp and the HOPE Foundation is setting up another, with new developments and extensions daily.

Do you feel you made a difference?

I have no false notions that I was able to change things on a massive scale in three weeks. But I think I made a difference in the lives of individual patients. Just to bear witness to the suffering of the most persecuted minority in the world – that was maybe the main impact of the work I did there. Assessment and treatment were almost secondary to building relationships and being part of the healing process for these men, women and children. I view this work as a struggle to uphold solidarity with the Rohingya people, as ethnic and religious minorities in the lands we call home.

Have you experienced discrimination at home?

It was not always easy in medical school. I experienced overt bigotry and Islamophobia. I remember during my third-year clerkship rotation, I couldn’t scrub in because of the hijab. There was no policy against it, but it was considered taboo to wear it in the OR. I would be left standing there with my exposed arms scrubbed up, humiliated as nurses and supervisors refused to let me don a sterile gown on the basis of my wearing a hijab, though their own surgical caps were not sterile. I’ve had supervisors who were openly bigoted and Islamophobic, some who violently criticized Islam and anyone who practises it. I’m not trying to compare that discrimination to what the Rohingya have faced in their homeland, but to a certain extent we are both visible ethnic and religious minorities. An important part of standing in solidarity with the Rohingya is being able to recognize and confront ethnic and religious discrimination here at home. It’s also a big reason why I think it’s important that patients see themselves reflected in their physicians. That said, I think we’re starting to see a move toward cultural safety, social justice and anti-oppression awareness and training in medical school. I recall a few problem-based learning sessions where this was the focus, and a few individuals in the Faculty are real champions of social justice and de-colonization, such as Dr. Lisa Richardson and Dr. Umberin Najeeb. But we need a lot more of that.

Just to bear witness to the suffering of the most persecuted minority in the world – that was maybe the main impact of the work I did there

Did that cultural affinity with the Rohingya enable the work you did?

It allowed me a seat of privilege into the lives of these people, which I would not have had otherwise. I would go into a home or tent and as a fellow woman, a Muslim of South Asian background, I could empathize in a way that others maybe could not. It’s incredibly important to understand the cultural context when working with vulnerable populations. One thing that troubled me was that some health-care providers and journalists were taking photos of women without their consent, while they were physically and emotionally exposed.

We get the privilege of meeting patients in what is for many the most difficult time in their lives, and we a have a responsibility to protect them. Many women were not told these pictures would be published and essentially shown to the world, and were under the assumption that only female health-care providers would see them. That is a failing on the part of health-care workers and the media. One of the favourite tactics of the Burmese military is to strip women naked and humiliate them, and when we take and share photos of their exposed bodies without their consent, we're victimizing them again.

Is there any move to stop that behaviour?

It’s difficult to create a concerted policy against it. There is still a lot of chaos with many actors including the government, military, and multiple NGOs working on the ground. I have suggested to the HOPE Foundation that a basic orientation be given to all volunteers, including the history of the Rohingya people and info on religious and cultural context. But it’s still one's personal responsibility to know this history and context before arriving.

What else can we do to stop this disaster?

People can educate themselves about the history of the Rohingya. They have lived in the area known as Rakhine state for centuries, and they are not illegal immigrants as the Burmese government would have us believe. They have been denied citizenship in Myanmar since 1982, essentially rendering them stateless. And there has been very little media interest until now, when it’s reached a critical mass. Sustained media coverage will be very important, but we need action, not just talk.

[Canada’s special envoy to Myanmar] Bob Rae’s report needs to have teeth, it can’t just be just a PR exercise and talking point. We need to discuss sanctions and an arms embargo. As a Rohingya father told me while he cradled the badly burnt body of his son: "The Burmese military and the civilians who backed them must be tried in an international court of law." It’s hugely important to support and get involved with Canadian NGOs working on the ground, like Islamic Relief Canada, a tight-knit organization that is helping those still trapped in Myanmar. And talk to your MPs. The Canadian public has a lot of power to pressure our government to stand up for what is right.

Hear more about this story on CBC's The Current: Doctor says world needs to know plight of Rohingya refugees

The Balukhali refugee camp's mobile health unit in Bangladesh