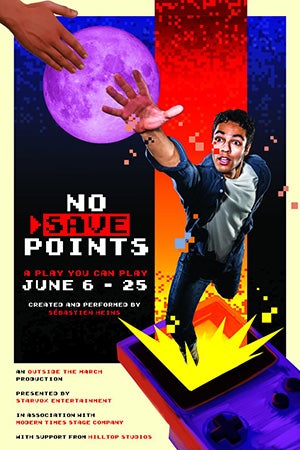

Artist residency at U of T helped actor Sébastien Heins develop innovative new theatre performance

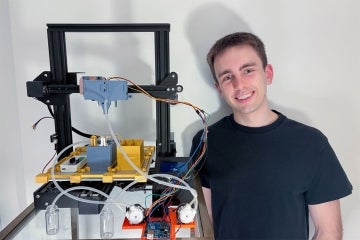

U of T Assistant Professor David Rokeby (right) is working with actor and former BMO Lab artist-in-residence Sébastien Heins on No Save Points, a stage show using cutting-edge technology (photo by Tara Maher and David Rokeby)

Published: May 4, 2023

An innovative new theatre production created by actor Sébastien Heins that was developed at the University of Toronto's BMO Lab for Creative Research in the Arts, Performance, Emerging Technologies and AI will premiere in Toronto in June.

David Rokeby, associate director and assistant professor, teaching stream at the Centre for Drama, Theatre & Performance Studies in the Faculty of Arts & Science, collaborated with Heins – one of BMO Lab's first artists-in-residence in 2020-2021 – on No Save Points, which runs from June 6 to 25 at Lighthouse ArtSpace.

The residency program is a partnership between the BMO Lab and Canadian Stage, in which two artists are selected to immerse themselves in the lab’s technologies and experiment with ways to apply them to live performance.

Rokeby and Heins also worked together on a workshop of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui by Bertolt Brecht in April 2022.

Video games, theatre and memoir collide in the fast-paced adventure narrative of No Save Points, as Heins places the control(er) in the hands of the audience – entrusting them to pilot his performance using state-of-the-art motion-capture and haptic technology.

“It's really exciting as an artist to be able to link up with somebody with as much experience as David,” Heins said.

“Oftentimes technology seems like an impediment, but interacting with somebody who is capable of turning technology into art inspires everybody to see technology as a fluid, very human tool.”

The use of a motion-capture suit was just one of the technologies Rokeby and Heins experimented with during the residency. The suit shadows a person's motions and sends information to a computer from sensors at 100 times per second – these sensors detect three-dimensional orientation and movement of the person wearing the suit. That data are then mapped onto a corresponding digital avatar or character that can be projected onto a screen.

The play's story was inspired by real-life events – following his mother's diagnosis of Huntington's disease, Heins found himself contemplating the loss of control such illness imposes on people's lives, bodies and emotions.

The situation reminded him of his childhood, when he would chafe against attending events with his parents and his mother would allow him the escape of playing video games on his Game Boy.

“I started to wonder how my love of theatre, video games and my mother could intersect,” Heins said. “I found myself wanting to escape from the truth of [her] diagnosis – and so the Game Boy became a symbol of taking back control.”

In the one-man show, Heins plays up to 10 different characters, using the motion-shadow suit, a hacked Game Boy and a controller to weave his way through the narrative of what happened to his family. Amid a series of monologues, the main character escapes into a game that represents the psychological processing of his experiences.

“The use of technologies as a metaphor here is really key, because it shifts it from being, ‘Here's a cool thing you can do,' to ‘Here is a way this character is working through things,'” Rokeby said.

“The best uses of technology and art are when they are not just as spectacle, but there is a metaphorical relationship to the content in the story so that the technology is adding to the texture of what the audience is thinking and experiencing, rather than just adding something cool.”

The audience has a key role in the show as well. The hacked Game Boy system allows an audience member to use a gaming controller to send signals to buzzers that are placed on Heins’ body through a haptic feedback system. Each buzzer tells Heins which direction to move in – or if he should jump or duck – in the video-game world, while those motions are reflected in a digital avatar representing Heins as his 10-year-old self. The scene is projected onto the show's set – a 15-foot-tall Game Boy.

Heins experiences the buzzer sensations as akin to receiving a text message on a cellphone in his pocket – and will be anticipating those signals during the performance so he can respond in the moment.

Rokeby describes such moments as similar to a sprinter in a race waiting for the starting pistol to go off – he notes the physical demands of Heins' show are incredibly high, but the usage of such new technologies in theatrical performance makes for an inspiring challenge.

As Heins and his theatre company Outside the March rehearse in preparation for No Save Point's opening in June, he will continue working with Rokeby to test the game on players to improve the audience experience.

“Having the mixture of a live performance in motion capture and this other world that the actor is also participating in creates this really interesting tension, which speaks to the fact that we now live so much of our lives at the precipice between the physical and the virtual,” Rokeby said.

“If played properly, that disjunction of the virtual and the real actor together speaks to a very contemporary experience.”