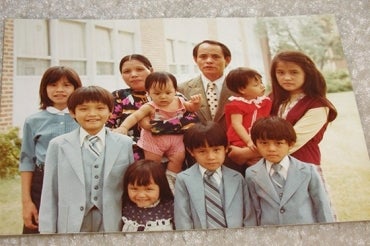

Associate Professor Nhung Tuyet Tran with her family in Michigan soon after arriving in America as a Vietnamese refugee. She is pictured standing in the bottom row with her brothers (photo courtesy of Nhung Tuyet Tran)

Published: April 5, 2017

By

With the renewed debate in Europe and North America over refugees, Bruce Kidd, vice-president of U of T and principal of U of T Scarborough, shared his blog this week with Nhung Tuyet Tran, associate professor of Southeast Asian history in the Faculty of Arts & Science.

She shares her story below about her experiences as a refugee escaping Vietnam, being in a refugee camp and eventually settling in the United States – first in Michigan and then Texas.

I never realized that I was an American patriot until I moved to Canada and before this year is over, I may become a Canadian patriot, though through a circuitous route. I rarely share my own story, in part because of my revulsion at the liberal elite’s desire to consume compelling struggles. I want to be known for my scholarship and teaching, a privilege that people of European descent in my field enjoy, rather than being reduced to a representation of the refugee experience. However, last year, in the midst of the largest humanitarian crisis of our times, the fate of Syrian refugees, I felt that it was irresponsible not to speak out.

I was born in Vietnam immediately following the end of the American War, to parents of modest peasant backgrounds. My parents had no formal education, but they could read and write. My father had been a soldier in the French colonial army and had lost his leg on a land mine sometime in 1953-54. My mother was from a moderately successful peasant family from the north, whose own grandparents were executed during the land reforms of 1956. In Saigon, they were among the million or so new migrants who placed pressure on the physical infrastructure of the new state, but also formed the locus of political support for the president of the new Republic of Vietnam, himself an ardent Catholic. Handicapped and uneducated, my parents did what they could to make do: my mother sold tofu on the streets of Saigon and my father took jobs here and there. In the 1960s, they benefitted from the influx of American capital, and alone or together, as memories are blurred, opened a small bar. At some point in the early 1970s, my mother’s hand was maimed when she intervened to protect a patron at the bar.

After 1975, the new Vietnam was not kind to two disabled, Catholic individuals whose migration south signaled a political betrayal. At that point, they had six children, and cared for two maternal uncles, who were teenagers at the time. Twice, they tried to commission escape, only to be turned in by family members. The third and final time, to conceal their efforts, my two eldest sisters, aged 10 and eight, traveled on the back of trucks and buses to a coastal city of no great distance, but seven hours away, to negotiate our family’s escape.

So it was, as the story has been relayed to me over the years, one summer day in 1979, my parents somehow got my six older siblings, my newly born three-month-old sister, my uncles, and me to that port town and on a wooden boat with other families. My parents had always maintained that this would have been our last try, that they had made their peace with the unknown beyond the shores of the South China Sea, or death for their children and wards. I have no real memories of the escape, but one vague manufactured one of the ship that rescued our family. A Norwegian ocean liner had spotted our tiny boat after a few days and we were taken onto it. Real or manufactured, my earliest memory is the sensation that I was stepping onto a steel boat as large as a city, and that automobiles could drive around it. The ship took us to the nearest refugee camp from our location, as the laws of the seas required, in Singapore, which is when my own memories emerge, sometimes with the help of photographic images, which remain the only evidence I have of my existence before the age of five.

In the image [directly] above, I am pictured with my brother in our refugee camp. My hair is freshly shorn to prevent the spread of lice among the refugees. The image [below] captures our arrival in Grand Rapids, Michigan. My father is on the far right and another one of my brothers is carrying his wooden leg. On the left, my mother is carrying my sister, who would have been close to one at the time. The [lead] picture [at the very top of the post] is, as far as I know, our first "family photo" with eight of the nine kids (I'm the girl in the front row), on one Sunday after mass in 1981 or so. My youngest brother had not been born yet. The picture reveals a happy and settled family, but it also obscures other stories, moments of great generosity on the one hand, but also exploitation and discrimination during our early years in the United States.We had been sponsored by a Dutch Reform Church, but with strings attached, it soon emerged. The picture captures a happy moment after mass, but also conceals the fact that we had just been evicted from our home, owned by the congregation, because we would not convert. In retrospect, the eviction seems all the more enraging because my parents, siblings and I had worked long hours harvesting blueberries on farms affiliated with the church. Despite the organization’s decision, a congregant, whom I remember as a tall man who used to take us out into the city, continued to visit. He helped us to apply for public housing and other assistance. One Christmas Eve, he even brought hand-me-down clothes, including my favorite, a Miss Piggy nightgown. Eventually, my parents moved us to Texas, and we left behind cold Michigan winters.

In Michigan and Texas, my family survived because of the government programs implemented to help the weakest among us. My mother worked 14 hours a day in a restaurant and my father did manual labour, but it was not enough. Between the ages of eight and 12, I de-headed and peeled hundreds and hundreds of pounds of shrimp, alongside my younger sister. The shrimp would then be sent to be packaged elsewhere and sold in gourmet stores around the country. My older siblings all worked part-time jobs, not for spending money, but to pay for essentials in the household. Still, it was not enough, and it was the public services for the poor that sustained us.

Despite our poverty, the Medicaid program, which provided basic medical care, ensured that in emergencies we would still receive prescription medications and acute care. The Food Stamp Program, a food-voucher system, did not satiate our hunger but did prevent us from starvation. The Housing Section 8 Program, which helped the poor find suitable housing, ensured that we were not homeless. With the small welfare stipend, my parents could pay rent and the gas bills so we did not freeze in Michigan, die of heat exhaustion in Texas or forego basic hygiene items like soap.

As our basic material needs were met at home, our intellectual and psychological needs were nurtured at school. Then, in the 1980s, the educational structure in the United States was good enough that we could attend our local schools and receive quality education. The federally funded university grant and loan programs allowed us to attend university. Throughout these years, we had to start over many times, twice because of robberies in our tiny home and another time when our house burnt down. We faced xenophobia, racism and inequality in our America, but we also benefitted from the incredible structural generosity of a nation and the personal generosities of others around us. From the bureaucrat who could have made our lives more difficult but instead gave us the benefit of the doubt, to the teachers who recognized our thirst for knowledge and sent information about enrichment programs to us. Personal generosities, however, were no replacement for that safety net, and it was our fortune to have the two that enabled us to survive.

Despite its failings, our America was one in which the poor had access to basic healthcare, a more compassionate immigration system and a solid education system. These institutions are essential in a fair society. Since the first weeks of this new administration, the President and the Republican-led Congress are dismantling it. They have drawn on language to turn Americans against one another, and it is only three months in.

Lucky as I am to enjoy a stable position in Canada, I have a responsibility to share my story as we see similar sentiments take shape here. The defunding of education in Ontario, and the stripping of programs to help the poor in cities across Canada, are muted examples of those American initiatives.

I share my story also, not only to resist the xenophobic, Islamophobic rhetoric, often accompanied by violence, that has been unleashed in the United States and in Canada, but to counteract language that is emerging from progressive circles, too. The distasteful discourse around the potential “brain surge” that may flow into Canada as a result of the travel bans in the United States directs attention away from the real suffering that these individuals face. Refugees and victims of religious discrimination should be welcomed because it is right to protect them against state-sponsored violence, not because they can help the bottom line. If I made any contributions to society, it is not because I had any promise as that young child in the refugee camp, it was because of those institutional structures.

As a teacher of the history of Southeast Asia, I retell stories of courage and cowardice that have shaped the contours of our modern world. I have never seen any person who has stood up and taken a stand against oppression regret it later in their lives, though there are many stories of those who turned away, and regretted it for the rest of their lives.

I believe that Canadians who enjoy the benefits of influence and position have a responsibility to take a stand and speak out against the injustices they see, whether south of the border or in our own communities. Canadian leaders should add substance to their rhetoric of fostering a just and inclusive society, by welcoming refugees not because they can become great citizens, but because it is the right thing to do. A living income, access to social services and equal access to education is what makes great citizens. As my neighbours, friends and colleagues work to bring Syrian refugee families to Canada, and to see how differently RCMP officials are greeting refugees fleeing the United States, I feel proud. However, I am mindful of how quickly public opinion can turn.

As I write this blog, I am also preparing my application for Canadian citizenship, so that in the next year or so, should my application be approved, I can exercise my civic duty to vote in local and provincial elections. My own father voted in every election from the time he became an American citizen to the day he died, on the morning of the 2002 mid-term elections. At the end of a lengthy illness, he was declared brain dead that morning. After he was gone, I collected his things and saw that after so many years, he still carried his voter’s registration card in his wallet. He had become an American patriot and exercised his most sacred of duties faithfully. Our elected leaders answer to us, and as citizens of a just society, it is our responsibility to demand it of our representatives.