What happens when non-western students attend western universities?

Published: October 15, 2014

Universities are increasingly global institutions – with large numbers of foreign students, study abroad opportunities for domestic students and even branch campuses in other countries – but what effect does the globalization of higher education have on students?

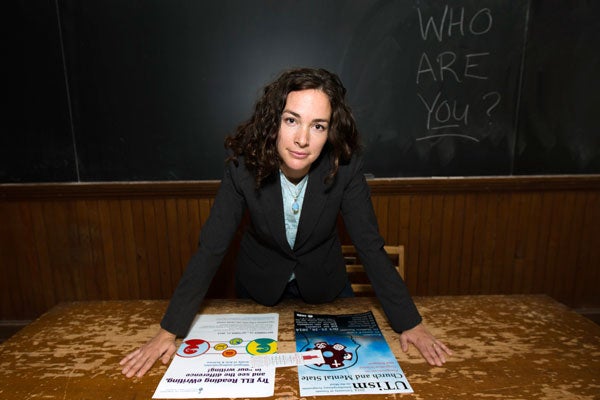

That’s what Grace Karram Stephenson, a PhD student at U of T’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), is trying to find out.

Karram Stephenson is looking at how students in non-western countries are affected by enrolling at branch campuses of western universities.

There are close to 200 branch campuses of western universities around the world and more are being established every year, often in countries where the cultural and educational values of the host country differ greatly from that of the university, she says.

“Do they [western universities] change their standards when they establish branch campuses? And the local cultures? Will they be changed?” she asks. “How are students' identities changed when they're enrolled in a program that’s very different from the culture in which they're actually living?”

To explore these questions, Karram Stephenson talked to students attending branch campuses of English and Australian universities in the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia. Her conclusion: students’ values and expectations change because of their experience at international branch campuses. They also sometimes struggle with conflicting familial and cultural demands.

This is especially true for female students, she says. “In first year, they're not really thinking about a career; by second year they've realized they're succeeding at university and they have an idea for a career, and they’re being told by their professors that there are all these amazing options. For these women it's an incredibly empowering experience but they face a lot of barriers from outside – their parents tell them that they'll be getting married as soon as they're done or their husbands are not open to them doing a master's degree or working, for example. How do we help these young women get the education they want without breaking their family ties?”

Karram Stephenson also found that students’ cultural values affected how they adapt to university. For example, Chinese Malaysian students tended to identify themselves as independent, high achievers who were used to examination style classes in high school.

“They hated first year (at the branch campus) because they were forced to work in groups, but by third year they enjoyed it.”

She says overall she’s hopeful that students will be able to adjust to the increasing internationalization of universities. “Students are good at navigating the divide between the university and the culture.” However, universities need to help the students, for example, through language training or workshops in understanding cross-cultural differences.

This isn’t the first time Karram Stephenson has looked at the impact of globalization on students. For her master’s degree at OISE she examined how studying abroad affected the spiritual values of domestic U of T students. The experience can often be transformative for students. “As they see their own culture through the eyes of foreigners, it is not uncommon for them to develop new identifies and question old ones.”

She says students studying abroad become more aware of the world’s complexity. “For the students traveling to Kenya, many returned home understanding new dimensions of poverty and the challenges of development work in Africa. Several of the students traveling to Ecuador mentioned that their own presence in the fragile environment was problematic. While the trip advanced their learning they feared it did ecological damage as well.”

Karram Stephenson’s interest in the globalization of higher education grew out of her own experience as a study abroad program coordinator in Fiji. Fiji’s population is roughly half indigenous Fijian and half south Asian. Indigenous Fijians could attend university for free while south Asians had to pay increasingly high tuition which led to the south Asian minority establishing its own university.

“This made me very interested in how students who are at the centre of these political decisions are affected. How do they come out?”

She continues to explore these issues through a regular blog at University World News (http://www.universityworldnews.com) and at OISE, where she’s now looking at how higher education helps facilitate the move of skilled labour between South Asia, the Gulf States and Canada. “That's my next exciting project.”

Terry Lavender writes about international affairs for U of T News.