U of T researchers wrap up 40 years of work, ensure legacy of once-renowned author

Published: August 5, 2016

For more than 40 years, an international group of researchers based in the Department of French at the University of Toronto has been reading Françoise de Graffigny’s mail.

Not just reading it, either. They’ve been collecting, transcribing and editing letters she sent and received to create the recently completed La Correspondance de Madame de Graffigny, a 15-volume print collection of more than 2,500 letters, published by the Voltaire Foundation in Oxford.

Before her death in 1758, Françoise de Graffigny was the world’s most famous female author, yet she was almost forgotten a century later. The letters reveal her most intimate thoughts as she went from being minor nobility in Lorraine, to a celebrated author and renowned Paris salon hostess. They also offer a glimpse into the intellectual, social and political history of 18th-century France, as well as valuable insights into the condition of women at the time.

A fitting tribute to founding editor

Work on the La Correspondance de Madame de Graffigny series was started in 1975 by the late Professor Alan Dainard (pictured below), who died in December 2014 after devoting almost 40 years as general editor of the project.

“It’s a bittersweet milestone since Alan did not live to see his project finished,” said Professor Emeritus David Smith, who has been on the editorial team from the beginning and served as volume editor for the final volume. “Madame de Graffigny’s Correspondance is his monument.”

Dainard is credited not only with realizing the abundance of historical and social information in the letters, but with building a team to embark on the project.

“He enjoyed the affection, loyalty, respect and admiration of all his fellow editors, his student assistants and his colleagues at the Voltaire Foundation,” said Smith.”His modesty was legendary and his generosity culminated in his establishment of a trust fund to ensure the continuation of the project after his death.”

Dainard was succeeded as general editor by English Showalter, Rutgers University professor of French and renowned Graffigny biographer, for the final print volume. Showalter was also there at the start, having been invited to join the team in 1975 following years of his own research on Mme de Graffigny’s life and work.

Who was Françoise de Graffigny?

Mme de Graffigny was born Françoise d’Happoncourt in 1695 and raised in Lorraine, then an independent duchy on the northeast border of France, into a life peppered with emotional and financial turmoil. She was married at 16 to an abusive alcoholic husband and all three of their children died of illnesses while very young. A widow at the age of 30 with few financial resources, she frequented the court of Lorraine, but when the ex-king of Poland became the new duke, she left for Paris, enjoying the hospitality of friends en route.

She eventually produced several plays and short stories but her greatest literary achievements came with the instant success of her 1747 novel Lettres d’une Péruvienne (Letters from a Peruvian Woman) and the very popular 1750 play Cénie. The novel – which saw 14 editions within a year of its release, and 133 by a century later – tells the story of a Peruvian woman living in France who is rejected by her Inca lover, then rejects her French suitor, and ultimately never marries.

It’s been said that the story was inspired by her own relationship with Léopold Desmarest, a cavalry officer with whom she had a long-term affair and who, after years of philandering and receiving financial support from her, left her for another woman. Though her letters mention one other brief but intense affair with Pierre Valleré, a lawyer who shared her Paris house and remained a loyal friend, she never remarried.

From obscurity to notoriety

Lettres d’une Péruvienne – and Françoise de Graffigny herself – regained prominence again in the 1960s, especially among feminist critics and historians, and the novel was frequently added to reading lists featuring 18th-century authors. U of T French professor Penny Arthur, another of the team of editors, sees in Graffigny an independent and confident woman who strove to improve her writing and to understand new ideas, despite her lack of formal education.

“Graffigny would have called herself a ‘femme d’esprit’ – a woman of wit,” said Arthur, who was volume editor for the 11th and 14th volumes.

For many, though, Mme de Graffigny’s letters to François-Antoine Devaux, a lawyer with literary aspirations who was her closest friend and confidant until her death, are considered her “masterpiece”.

In her correspondence with Devaux she wrote candidly about disparate topics including a three-month stay with writer and philosopher Voltaire and his mistress, aspects of her health, and artistic rivalries. She also described her affair with Valleré in detail, about how she was as baffled by his affection and attentiveness as she was by the sexual experience, and how she rejected his efforts to control her life.

In the letters, her writing is spontaneous and unrehearsed, providing a magnificent example of everyday language during the period.

A digital coda to ensure her legacy

The completion of the print edition also brings to an end the fascinating story of Françoise de Graffigny’s lost papers which began more than 250 years ago. (ED NOTE: see below for full story.) The project will wind down over the next few years with an online-only 16th volume edited by Arthur that will include a cumulative index, additional documents and corrections.

“Volume 16 is an integral part of the whole edition and will aim for the same high standards of scholarship shown in the print volumes,” said Arthur. “The Voltaire Foundation, like other academic publishers, is moving from print format to digital, and academic libraries are relying more on digital resources. This format lends itself well to indexing, corrections and additions, because it can be continuously updated.”

With files from the Voltaire Foundation, University of Toronto Magazine and Rutgers Focus

________________________________________

The Story of Madame de Graffigny’s Lost Papers

- François Devaux inherited all of Françoise de Graffigny’s papers following her death in 1758.

- Devaux died in 1796 without publishing them as he had promised years earlier.

- The letters were kept by Devaux’ descendants and eventually sold around 1820, with the majority of them ending up in the hands of English bibliophile Sir Thomas Phillipps.

- Phillipps’ collection resurfaced again at an auction in the 1960s – long after Phillipps’ death – and were purchased by New York bookseller H.P. Kraus; Kraus sold to the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York the letters describing Graffigny’s stay with Voltaire, and donated the remainder to Yale University.

- Professor English Showalter of Rutgers University, who later joined the editorial team, saw the Graffigny Papers at Yale in 1969, and in 1971 a graduate student in the U of T Department of French independently discovered in the collection a volume of letters to Graffigny by her niece.

- Soon after, Alan Dainard made plans to edit the entire collection and began to assemble an editorial team to embark on the project.

- The first volume in the series was published in 1985.

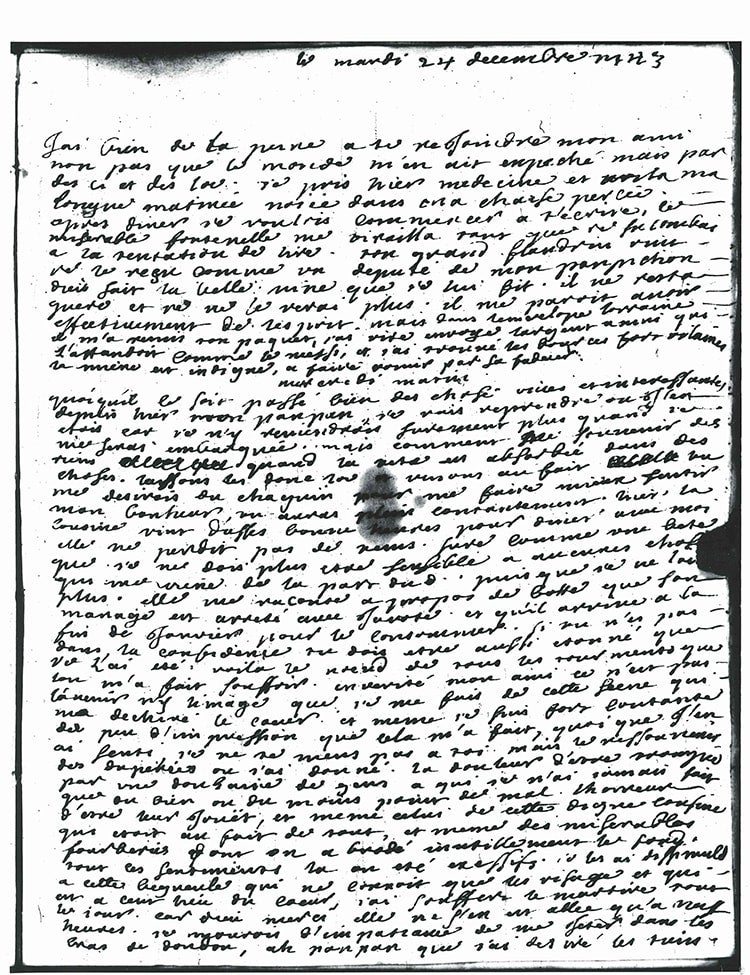

The first page of Mme de Graffigny’s December 24, 1743 letter to François-Antoine Devaux is pictured below. Each of her letters to Devaux were three to four pages in length.