U of T researchers mobilize resources to produce equipment for health-care workers

Published: April 15, 2020

A multi-disciplinary team of researchers has launched a project to co-ordinate and deploy equipment from across the University of Toronto to produce medical supplies like masks, face shields and ventilators for health-care workers on the front lines of COVID-19.

The Toronto Emergency Device Accelerator (TEDA) initiative draws on the resources of U of T and affiliate hospitals to: identify the greatest areas of need; co-ordinate equipment like 3D printers, laser cutters and water jets; and produce equipment that meets health and safety standards and can be used by health-care facilities in the fight against the novel coronavirus.

The group’s first order of business is to address one of the most pressing equipment needs presented by COVID-19: reusable face shields. TEDA has committed to producing 3,000 face shields in an effort spearheaded by Nicholas Hoban, a lecturer at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. Hoban, who is also the co-ordinator of the faculty’s digital fabrication lab, has cut models for the face shields, with production beginning this week.

Matt Ratto, an associate professor at the Faculty of Information who is coordinating the 20-strong team of professors involved in TEDA, says his desire to set up the initiative was influenced by his experience working on 3D-printed prosthetics.

“I watched as the initial enthusiasm for producing prosthetics through home 3D printing quickly turned into disillusionment as relevant clinicians were not looped into the processes of design and development,” says Ratto, who is chief science officer at Nia Technologies, a social enterprise that helps rehabilitation clinics in the developing world produce 3D-printed prosthetic legs.

“I didn’t want to see what happened with 3D-printed prosthetics occur again in this [COVID-19] space.”

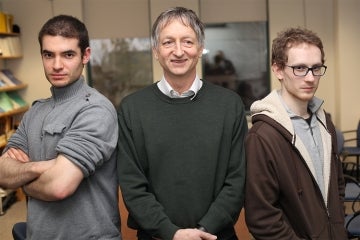

Matt Ratto, an associate professor at U of T's Faculty of Information, is co-ordinating the Toronto Emergency Device Accelerator (TEDA) initiative (photo by Nick Iwanyshyn)

With nearly two million confirmed cases of COVID-19 around the world, the rapid spread of the disease has left health-care facilities in Canada and elsewhere scrambling to secure personal protective equipment and medical devices for front-line workers.

Ratto says fabrication technologies like 3D printers can help meet the demand for some of this equipment, but stresses the importance of maintaining quality control and ensuring clinical needs are being met. To that end, TEDA counts several hospitals among its partners, including Toronto General Hospital, the Hospital for Sick Children and the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Mike Doell, an industrial designer from Ross and Doell Inc., edits the digital laser cutting file from the parking lot of the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design

(photo by Nick Iwanyshyn)

Meanwhile, Kamran Behdinan, a professor in the department of mechanical and industrial engineering in the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, is working to design and manufacture assisted bag ventilator devices – equipment that isn’t in short supply at present, but could become scarce if the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations continues to increase.

Behdinan (left) says these low-cost devices could be useful as “last-resort ventilators” that take the place of manually inflated ventilators that are operated by hand by nurses and paramedics.

“We want to make the mechanism as simple as possible, with a minimum number of components, using off-the-shelf parts and easy to fabricate and assemble, so that it’s easily scalable and we can use it on a mass scale if we need to quickly,” says Behdinan, who is director of U of T’s Institute for Multidisciplinary Design & Innovation.

The devices are designed to meet key respiratory parameters, and have features such as the option to be manually operable when required.

Behdinan and collaborators at the department of mechanical and industrial engineering have already carried out a rapid trial and have created a working prototype, using equipment including water jets. He is now working with experts at Toronto General Hospital to prepare an advanced device for clinical trials.

“If this gets out of control – hopefully not – they’ll need something to not get caught off guard, and I’m extremely optimistic that this can be a back-up solution,” Behdinan says.

The TEDA project will also generate supporting documentation and instructional materials, which Associate Professor Nadia Caidi (left) of the Faculty of Information says are critical to safe use of the equipment.

The TEDA project will also generate supporting documentation and instructional materials, which Associate Professor Nadia Caidi (left) of the Faculty of Information says are critical to safe use of the equipment.

“While the engineering challenges are really important and critical to the success of this project, it doesn’t work if people are not also told how to use and engage with these technologies,” says Caidi. “The work I’m involved in alongside colleagues is to look at the interface between the engineering aspect and human factors, and the user side – and ensure that, in addition to devising safe devices and products, we’re also providing safe and correct information.”

Caidi says the documentation will include manuals for health-care professionals who use and maintain the equipment, as well as instructional materials for engineers and fabricators who want to borrow the U of T designs to manufacture medical equipment.

“It’s not only about creating, producing and designing the supplies, but also about creating the metadata around them to ensure that anybody else who would like to reproduce them with their own equipment down the road can do so safely and effectively,” Caidi says.

She adds that the group plans to eventually provide the documentation in languages beyond English to expand their reach.

The TEDA project will generate supporting documentation and instructional materials, which researchers say is critical to ensure safe use of the equipment (photo by Nick Iwanyshyn)

The broad scope and cross-disciplinary nature of the TEDA project is something that Ratto, the project’s lead faculty member, says is a testament to U of T’s ability to harness its diverse strengths to respond to urgent challenges.

“We have so much expertise in all sorts of disciplines and groups,” he says. “We have engineering, we have clinical, we have social sciences, humanities ... the impetus was to really leverage U of T as a great site for co-ordinating this activity and carrying out this work.”