Turkey referendum follows global shift to the right: U of T historian compares the Erdoğan win to Trump and Brexit

Published: April 19, 2017

Following President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's referendum win earlier this week which has expanded his hold on power, members of Turkey’s political opposition were arrested in dawn raids today.

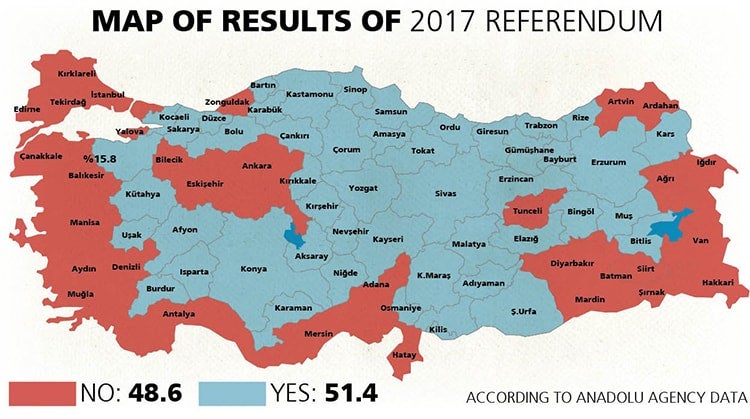

Erdogan has claimed a narrow 51.4 per cent to 48.6 per cent victory in the referendum, and protesters have been marching in the streets against what they're calling a rigged election. Lawyers and relatives of the detained told The New York Times that at least 38 people accused of participating in the protests were rounded up Wednesday morning or issued arrest warrants.

Jens Hanssen, an associate professor of Arab Civilization at the University of Toronto Mississauga and modern Middle Eastern and Mediterranean history at U of T's downtown Toronto campus, says the narrow win is “reminiscent” of the Brexit referendum and the American elections last year.

U of T News spoke with Hanssen about Turkey's future and the similarities between Erdoğan, U.S. President Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin and France's Marine Le Pen.

What do you think these results mean for Turkey?

What do you think these results mean for Turkey?

The constitutional referendum on Sunday has clearly split the Turkish public. The narrow victory of the ‘Yes’ camp is reminiscent of the Brexit referendum and the American elections last year. There also appear to be parallels regarding the demographic composition of each vote. Residents in major Turkish cities voted for the existing parliamentary system and the rural population generally for the adoption of a presidential system.

Whereas in the U.K. and U.S. the victories for the leave-campaign and Donald Trump came as a surprise if not shock to the system, the real surprise in Turkey was just how close the vote was, and how valiantly the democratic forces campaigned in the face of intimidation and reprisals.

Recall the June 2015 parliamentary election which saw Erdoğan’s “Justice and Development Party” (the AKP) lose its majority for the first time since coming to power in 2002. Unhappy with the result, Erdoğan held another, snap election for November 2015, launched major military offensives against the Kurdish region and criminalized the progressive parties that had gained popularity.

These elections restored his party’s majority but political violence spiraled. Since the coup attempt in July 2016 and the subsequent emergency laws that have just been extended for another three months, Erdoğan has purged tens of thousands of politicians, bureaucrats and military officers in an unprecedented form of Turkish “Gleichschaltung.” His government has arrested scores of journalists, closed independent media outlets and banned art exhibits and cultural festivals. Hundreds of Turkish academics have been jailed, many for signing the Academics for Peace Petition that I and many others in the U of T community also signed at the time, which called on the government to end its crackdowns targeting Kurds.

The signs are worrying. A new form of political system is spreading across the planet. In my view, the points of comparison are right-wing take-overs in the U.S., the U.K. and perhaps soon in France. In all cases, the xenophobe rhetoric of their supporters glosses the now familiar process of accumulating political power for the purpose of economic appropriation.

What will Turkey look like with Erdogan maintaining a stronger grip on power?

Against this background of a near-total gutting the once-thriving Turkish civil society, the referendum was supposed to facilitate Erdoğan’s anti-democratic policies for the ‘greater good’ of national unity. Instead, Turkey’s political and economic future looks more ominous than ever. Erdoğan now has the formal democratic mandate to unhinge the checks and balances between the executive, legislative and juridical levels, and at age 63, is set to rule for possibly two decades – without the approval of parliament, if necessary.

Do you think the results are accurate?

Yes, the vote count appears to be accurate. But we are receiving mounting evidence of irregularities both from international election observers and the opposition parties.

Moreover, under current law – which the referendum is supposed to cancel – the president of the Turkish Republic should not have participated in the election campaign and remain above party politics. Instead, this referendum has been all about Erdoğan. I suspect nothing will come of the protests since much of the independent judiciary has already been purged. In fact, the mood in Turkey is somber, even Erdoğan supporters are not celebrating that much. This is a result that no-one wanted, in a sense.

What will this mean for the region and stability in the area?

The EU and NATO are unlikely to do much. Both are too dependent on Turkey, not least because Erdoğan is using the specter of Middle Eastern refugees as political blackmail. He will keep bombing Kurds, and all kinds of militants will seek to destabilize Turkey and provoke Erdoğan to escalate the violence at home and abroad.

How do you feel about Trump making the first congratulatory call to Erdoğan?

Trump and Erdoğan are very similar, so are Putin, Netanyahu and Marine Le Pen.

So we are facing an albeit disunited authoritarian front globally. Democracies are being highjacked by chauvinists who will militarize their economies and cause mayhem in their countries and internationally. Things will get a lot worse before this phase has run its destructive course.