Social distancing and blame: U of T researcher on lessons from past pandemics

Published: March 26, 2020

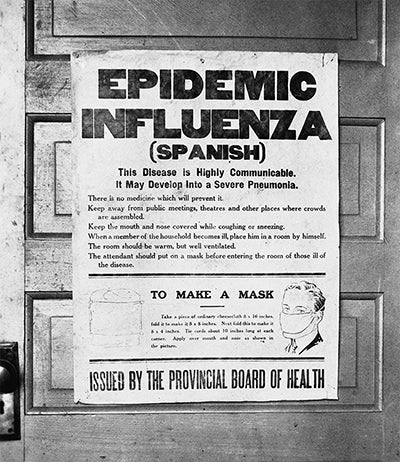

Public meetings are banned. Theatres, schools, colleges and churches are closed. Business hours are restricted across Canada.

It sounds like the current state of affairs. But it also happened in 1918.

While our experiences today with COVID-19 may seem unprecedented, there are clear lessons to be learned from pandemics past, according to University of Toronto Mississauga anthropologist Madeleine Mant.

“Most folks I know haven’t seen anything this intense,” she says. “I certainly haven’t in my lifetime. But if we talk about 1918 influenza, none of this is new – it’s just faster and different.”

Much of the response to the 1918 pandemic, also known as Spanish flu, sounds familiar. Mant says some Canadian towns started to attempt total quarantine and the province of Alberta made it compulsory to wear a gauze mask when outdoors. Business owners suffered, too.

In fact, people today are facing many of the same challenges and are offering the same critiques they did 102 years ago. Mant points to an anonymous letter in a newspaper in 1918 where the writer references businesses closing at 4 p.m. to help fight the flu, writing, “Is the flu germ more active after 4 p.m. than previous to that hour?” Similar commentary can be found today as businesses restrict their hours.

When businesses in 1918 had to shut down for a time, there were calls to the government to help small businesses with “sickly trade and bruised feelings,” Mant says.

The 1918 influenza outbreak was unusual in that it killed so many people, including those between 20 and 40 years old.

“Pandemics are difficult emotionally as well as biologically for a lot of different reasons,” Mant says. And they have “incredible effects on history.”

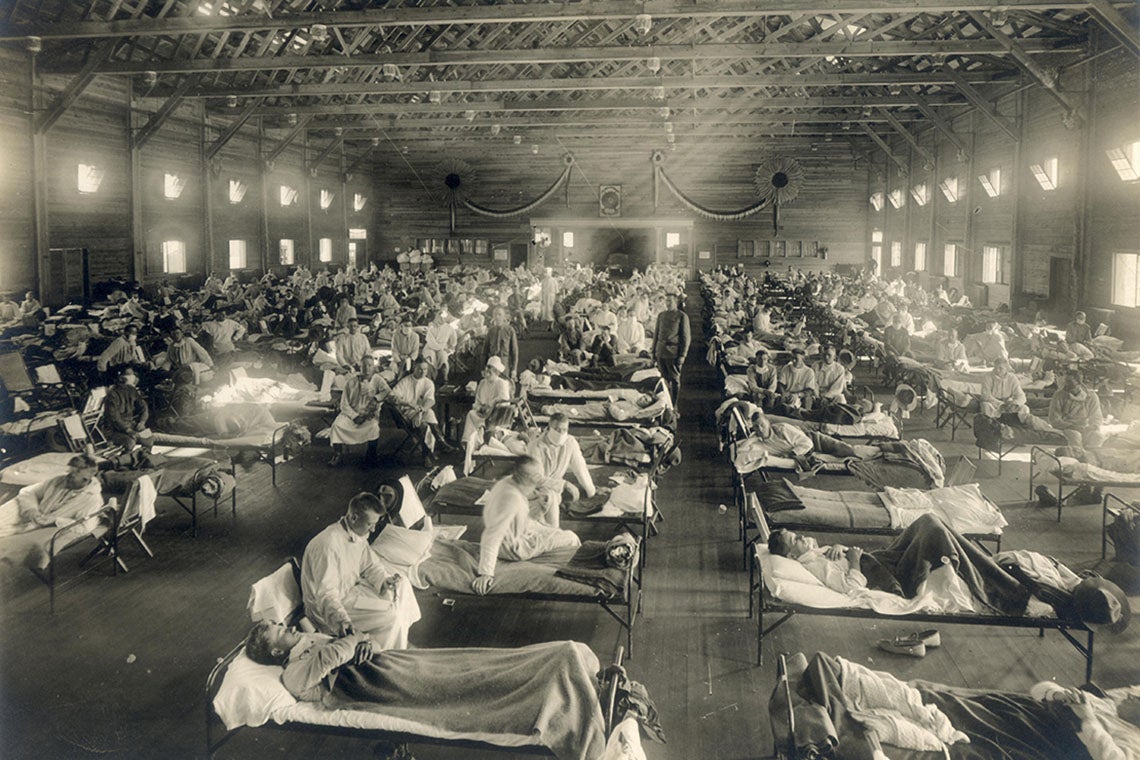

An emergency hospital at Camp Funston, Kan., cared for large numbers of soldiers sickened by the 1918 flu (photo via National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC. Image number NCP 1603)

Shame, blame and stigma often go hand-in-hand with pandemics. A good example of this is syphilis, Mant says. It emerged as we now know it in the 15th century when Italy and France were at war. As soldiers disbanded, they returned to their homeland, bringing syphilis with them, leading to an epidemic in Europe.

Everyone needed to name the disease, Mant says, explaining the French called it the Italian disease, the Germans and Italians called it the French disease, the Russians called it the Polish disease, while the Polish called it the German sickness.

“We immediately get a sense that everyone is saying it’s coming from somewhere else. It’s not our fault. This dirty disease we’re connecting to sexual behaviour is someone else’s fault,” Mant says.

Of course, we know it’s really a bacterium, but suddenly it means something socially, she adds.

This same pattern of blame can be found when the bubonic plague, caused by bacterium transmitted by fleas on rats, spread through the trade routes. Also known as the Black Death, the disease was scary because it could kill anyone, rich or poor, and there was no acquired immunity.

“What’s important about Black Death in the 14th century is we immediately start to see stigmatized groups being punished,” Mant says. “We see stigma played out in very terrifying ways.”

She explains there was a belief that God was punishing people. Jewish individuals and sex workers were targeted, with records showing vulnerable and marginalized individuals being burned alive because people thought that if they got rid of the “sinners”, God would stop punishing them.

The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s also saw the use of language that targeted specific groups.

The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s also saw the use of language that targeted specific groups.

“I hate saying this part of history because it’s so deeply offensive, but we have to talk about it,” Mant says before explaining that when it first emerged in the United States, HIV/AIDS was known as GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) and 4H, which stood for homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs and Haitians.

Calling it “emotional and awful language,” Mant says the government was essentially telling people their lifestyles and who they were was making them sick.

As the world grapples with a new virus, the language being used to describe this faceless foe is important.

“When we have people insisting on calling COVID-19 “the Chinese virus,” that is language being used as a weapon and we can’t ignore it,” Mant says. “It’s not even being subtly racist. It’s just openly stigmatizing.

“There’s a moral imperative that we keep each other safe. That’s the really important thing we can learn from these past pandemics. Countries and societies can certainly pull together, but we will slow ourselves down if we spend time blaming.”

While we’re once again seeing something scary in 2020, things are different, Mant says. With mass communication we can get information to people faster than ever before and co-ordinate large-scale actions. We have knowledge of the infectious agent, we know what it is and well-stocked labs are working to combat it.

“What we need now are the effects of small-scale cumulative action,” Mant says, referring to social distancing, grabbing groceries during off-peak hours and staying home as much as possible. “Disease has been with us since we’ve been around and it’s not necessarily going to go away, but our actions can ensure that the effects are not catastrophic.”