'A silent killer': U of T's Miriam Diamond on what COVID-19 has taught us about climate change

Published: May 6, 2020

As the outbreak of COVID-19 grew into a global pandemic earlier this year, countries attempted to stem the spread by restricting travel and issuing shelter-in-place orders. At the same time, economic activity slowed as businesses and factories cut back their operations or closed altogether.

As a result, scientists are now observing remarkable reductions in air pollution and carbon emissions around the world.

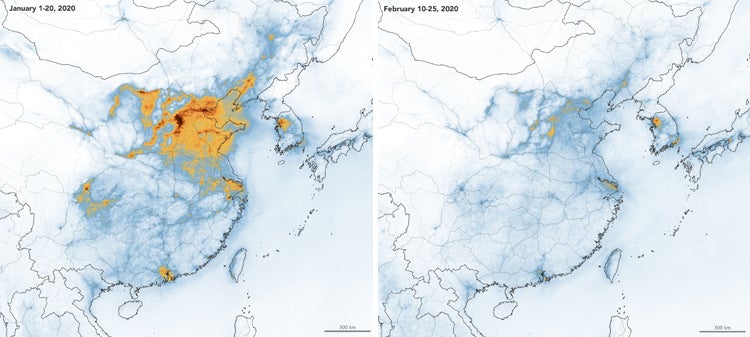

Levels of nitrogen dioxide – produced through the burning of fossil fuels – have dropped dramatically around the globe due to a reduction in vehicle traffic and industrial activity. In China, carbon emissions fell by 25 per cent in February. And Columbia University researchers measured dramatic drops in carbon dioxide and methane – two greenhouse gases – in Manhattan.

Levels of nitrogen dioxide – produced through the burning of fossil fuels – have dropped dramatically around the globe due to a reduction in vehicle traffic and industrial activity. In China, carbon emissions fell by 25 per cent in February. And Columbia University researchers measured dramatic drops in carbon dioxide and methane – two greenhouse gases – in Manhattan.

Miriam Diamond is a professor in the department of Earth sciences in the Faculty of Arts & Science. Her research focuses on contaminants and chemicals, how they enter and affect ecosystems and humans, and how her work can inform policy-making.

Writer Chris Sasaki of the Faculty of Arts & Science recently spoke to Diamond about the pandemic’s impact on air pollution and carbon emission levels – and what we can learn from it.

What does the drastic improvement in air quality and reduced carbon emissions during the pandemic tell us?

It’s shown us the connection between economic activity and air pollution in a very stark way. We’ve seen this before. For example, during the Olympics in Beijing restrictions were imposed on industrial activity and vehicular traffic in order to improve the air quality for the athletes – and it worked. And in 2008, we saw a reduction in air pollution and carbon emissions as a result of reduced industrial activity during the economic downturn.

What we’re seeing today is the same thing happening on a global scale. And when we see improved air quality in Toronto, Beijing, Paris – it drives home how much we pollute our environment and how, as a result, we are causing illness and premature deaths.

Images of China show levels of nitrogen dioxide in January, at left, and February, at right (photo via NASA/European Space Agency)

What are the health costs of air pollution and climate change?

Health Canada estimates that there are almost 15,000 premature deaths in Canada annually that are attributable to air pollution. And Marshall Burke from Stanford University has estimated that because of the decrease in emissions during the pandemic, there will be 50,000 fewer deaths related to air quality in China.

Of course, no one should be thinking of the latter statistic as a positive trade-off or silver lining. No one wants anyone to die. But it is a remarkable comparison that underscores the impact of air pollution as a silent killer.

And it’s not just air pollution. Climate change kills people, too, through heatwaves, flooding, fires and droughts. There is also a connection between climate change and exacerbated scarcity, internal displacement and migrations of populations.

Climate change has a huge price tag. It’s often described as an environmental issue but it’s not. It’s a matter of life and death.

The air pollution and climate crisis are arguably greater threats than COVID-19. Why haven’t we mobilized to fight them in the same way we’re fighting the pandemic?

We haven’t because climate change acts in many different ways, as opposed to a virus. Climate change is also slower moving and so it’s easier to disregard when we have competing interests for our attention and resources. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that we do an amazing job of protecting ourselves, but more so when a danger is immediate.

Also, there’s been a well-orchestrated effort to cast doubt in the minds of the public about climate change, how it presents a human health risk and how it links to, for example, extreme weather events. And so, I don’t think those experts are given the same level of respect as the health experts we’re listening to during the pandemic.

What would you most like to see happen with respect to air pollution and climate change as a result of the pandemic? Are you optimistic changes will happen?

Now is the time to restart the economy in a smart way that will ultimately save lives in the future. We have to continue to pursue a low-carbon society by investing in low-carbon technologies and by reducing our energy and resource demands to sustainable levels.

I see many things that make me optimistic. The pandemic has engaged the public in an unprecedented way. The vast majority of Canadians have become students, learning about difficult concepts like exponential growth and seeing how physical distancing – though it has a delayed effect – is nonetheless necessary. So it’s not just about what’s happening today – it's about the future, and that’s a critical thing to understand in addressing climate change.

Canadians are learning why experts matter. They’re listening to the advice of public health officials and scientists. And our politicians have for the most part been listening to those experts, following their recommendations and making evidence-based decisions.

It’s remarkable and it makes me proud to be a Canadian. I think this is what we need to embrace now and in the future.