M is for Mystery: The secret science of World War II

Published: June 20, 2016

So begins "Dial M for Medicine", Dean Trevor Young's introduction to the Summer 2016 issue of the award-winning Faculty of Medicine Magazine, which this issue focuses on medical mysteries. Over the next few weeks, U of T News will reprint some of the stories from that issue. Our first mystery, the Secret Science of World War II, is solved by freelance writer and U of T science graduate John Lorinc.

In August 1941, moviegoers flocked to the latest Hollywood war flick called Dive Bomber, which hit theatres months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The film tells the tale of two men — a Harvard-educated doctor and a seasoned pilot — searching for solutions to the altitude sickness and blackouts that afflicted pilots on dangerous missions. The unlikely pair defied the skeptics and experimented with a “pneumatic belt” meant to keep blood flowing to the brain. The film, audiences were told, was dedicated to the cause of “aviation medicine.”

Toronto audiences likely had no idea that the story was an almost eerily accurate retelling of the pioneering, super-secret aviation medicine experiments carried out by University of Toronto researchers at a Royal Canadian Air Force facility on Avenue Road north of Eglinton.

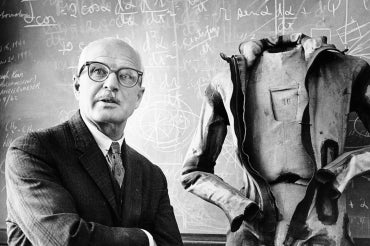

The facility was located on the grounds of the former Eglinton Hunt Club, which the RCAF bought for $50,000 to run its training programs. Inside, Professor Wilbur Franks (BA ’24, MB ’28), a U of T cancer researcher working for Sir Frederick Banting (MB ’16, MD ’22), used a human centrifuge to test the anti-gravity suit he’d designed for air force pilots prone to blacking out from intense g-force pressure created by tight turns and nose dives.

The suit, which he personally tested at Camp Borden, west of Barrie, Ontario, and later at the Farnborough Airfield in England, was the first of its kind and established Franks as a pivotal figure in the history of aviation medicine. But its development exacted a heavy toll: Banting, one half of the team credited with the discovery of insulin, was killed in a crash in early 1941 in Newfoundland while heading to England to test Franks’ invention.

So what exactly does an anti-gravity suit protect the body from? When someone is sitting at ground level, not moving, the earth’s gravitational field exerts what’s called a 1-g force, equivalent to the weight of that person. But when the same individual is being whipped around on a tight curve on a roller coaster, for example, inertia causes their body and blood to move along the original trajectory, resulting in a sudden increase in centrifugal force.

Scientists say that when this increased pressure is double the g-force of a resting body, the individuals’ weight at that moment is effectively doubled. At a high g-force, the weight of blood may be several times higher than at rest. The heart, in turn, strains to pump the blood around the body, especially out of the lower extremities and into the brain. Under this g-force strain, an individual experiences reduced vision, temporary blindness and finally loss of consciousness — a condition known as static hypoxia.

According to a 2004 article in the Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education and Research, the increasingly powerful fighter planes that were being developed during the interwar period seemed to be causing more accidents with pilots blacking out at the controls of aircraft that were flying higher and faster than ever before.

In the late 1930s, with the war in Europe looming, Banting realized that aviation medicine could play a strategic role in a conflict that would see increased use of bombers and fighter planes. His interest wasn’t incidental: Banting had served as an army surgeon in World War I and remained an officer in the reserves after the armistice of November 11, 1918.

Working with the RCAF, Banting moved to create an aviation medicine research team at U of T and tapped Franks, whom he’d met through a mutual friend of Charles Best (BA ’21, MA ’22, MD ’25). At the time, Franks was doing cancer research, which involved the use of a centrifuge for samples. He had noticed that glass test tubes tended to shatter in the device. But when he packed the tubes in water, they were fine.

Seconded to Banting’s project, Franks began thinking about the significance of this modification of a testing technique, and realized the water around the tube created sufficient hydrostatic pressure against the tube to counter the centrifugal force. Perhaps, he thought, the same principle would apply to human tissue.

After experimenting with mice at the Banting Institute, Franks in 1939 began developing a rudimentary version of an anti-gravity suit, which was lined with fluid-filled pockets and designed to fit snugly around a pilot’s legs and torso. To fund the research, Banting had approached an eccentric construction magnate named Harry F. McLean for a $5,000 grant. McLean, an aviation buff who once set out on a round-the-globe flying mission with his personal nurse, was known for wandering around in public, giving away large sums of cash or cheques.

Early in 1940, according to “The Remotest of Mistresses,” Peter Allen’s 1983 biographical essay on Franks, the researcher took a bespoke version of his invention to Camp Borden and went up with a RCAF pilot. Allen, a commercial flyer and accountant who first met Franks in the mid-1970s, writes that Franks had never even flown before, “much less endured high G aerobatic maneouvers.” But he and Banting were both fearless, and seized with a sense of mission (they had enlisted after Canada declared war and were given officer ranks). “It was their mentality,” Allen said in a recent interview. “They just did stuff that was risky.”

“In the airplane, I was sitting down,” Franks told Allen. “[W]hen the pressure hit, I thought [the suit] was going to cut me in two.” Wing Commander D’Arcy Greig, an ace Royal Air Force pilot, also tested the suit during secret flights at Malton in early June 1940. He came to similar conclusions. Allen quotes Greig’s report in his 1983 essay: “The suit in its present form is not a practical proposition.”

Interestingly, German scientists as early as 1931 had arrived at a the same impasse with their own version of an anti-gravity suit for pilots. They opted to discontinue their research program.

Realizing that they needed to refine the invention, Banting and Franks persuaded the RCAF to partner with U of T and Victory Aircraft (later Avro) and build a human centrifuge at the Hunt Club facility in 1941. Jordan Bimm, a PhD candidate at York University now completing a doctorate on the history of aerospace medicine, says the centrifuge looked like a giant stand mixer, with an air-tight gondola that could hold one person. The gondola’s temperature, air pressure and orientation could be altered, with internal sensors monitoring performance. (There are photos of Franks himself in the centrifuge, which was in operation until 1987.)

Franks reckoned it was possible to scale down the suit, so the coverage was limited mainly to the legs and buttocks. Bimm says Franks made numerous versions of the suit, up to “Mark 7.” “They refined it many, many times.” U of T historian Michael Bliss (BA ’62, MA ’66, PhD ’72), in his biography of Banting, described him and Franks as “tinkerers.”

“They tried things,” Allen says. “Sometimes it worked, and sometimes it didn’t.”

Following Banting’s tragic death in February 1941, Franks finished developing the suit sufficiently, such that the Royal Air Force was prepared to use it in combat. But the Allies regarded the discovery as so significant that they didn’t want to fly sorties over Europe, for fear of losing a plane operated by a pilot wearing the “Franks Flying Suit.” If the Germans captured the flyer, the RAF thought they could reverse engineer it.

Instead, RAF pilots wearing Franks’ invention were sent to North Africa to provide air support for US General Dwight Eisenhower’s invasion of Algeria in 1942. The results, Bimm says, were mixed:“They found it difficult to move around.” US researchers took over.

But senior American aviation medicine experts later told Franks his pioneering work was critical in the refinement of the technology. The work in Toronto, moreover, paved the way for the Canadian military’s sustained investment in aviation research at CFB Downsview, which continues to this day. “That traces right back to the decision to make this a competency in Canada,” says Bimm.

The military didn’t declassify information about the Franks Flying Suit until the 1950s, and Franks himself remained a low-key medical researcher until the 1970s, when, Peter Allen heard him lecture at U of T about the invention. He decided to make it his mission to ensure that Franks was duly recognized for an achievement that has reverberated through the post-war history of military flight. “Franks was a very understated man,” Allen reflects. “He just thought he was doing his job.”