But is it literature? U of T experts on Bob Dylan's Nobel Prize

Published: October 14, 2016

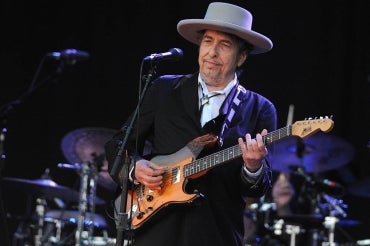

The Swedish Academy stunned the world and delighted music enthusiasts of many generations on Thursday by awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature to celebrated singer-songwriter Bob Dylan.

The news is making headlines here at home and around the world. (Read U of T's Ira Wells in The Globe and Mail and The National Post)

U of T News spoke to Robin Elliott, professor of musicology and Jean A. Chalmers Chair in Canadian Music; Don McLean, professor and dean of the Faculty of Music; Ken McLeod, associate professor of music and culture at U of T Scarborough; and Ira Wells, a sessional instructor in American literature in the department of English.

Is this a surprising award?

Ira Wells: It is rare for an American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. The last was Toni Morrison in 1993. And obviously Dylan is the first pop singer. Many recent Nobel literature laureates have been niche figures, known only in literary circles. It is rare that you get a celebrity on these lists, especially someone of Dylan’s magnitude.

Ken McLeod: I think it’s wonderful that a singer-songwriter has been recognized for the quality and impact of lyrics. Going back to the ancient Greeks, the great narrative epics were accompanied and enhanced by music. The ability to write literature and/or poetry as an adjunct to music has been highly prized in classical music from the criticism of Robert Schumann, the narratives of Berlioz and, perhaps most prominently, in the works of Richard Wagner, who is celebrated for having written both the texts and music for his music dramas.

But do lyrics on their own count as literature?

Ira Wells: There is a relatively simple way of addressing that question. Do the lyrics yield multiple interpretations? Is it possible to read these lyrics and come up with multiple interpretations that would reward serious, close reading? That is a baseline for a university professor deciding whether or not something counts as literature. It is indisputably the case that Dylan’s best songs – "Like a Rolling Stone," "Visions of Johanna," "Every Grain of Sand" – meet this threshold.

Don McLean: Popular-music lyrics across a wide range of genres make up arguably the most significant poetic form of the 20th and early 21st centuries. Lieder and folksong-derived nationalisms of the long 19th century remained confined largely to arts-circle and upper-middle-class elites. Sound reproduction paved the way for the radio and record industries, without which the ubiquity of popular music is unthinkable. For many, American and British popular music became the iconic poetics and affective underpinning of the age, which is in part why relationships to music and artists are so nostalgia- and memory-driven.

Ken McLeod: In an age of – I would argue – declining emphasis on meaningful lyrical content in popular music, it is nice to see that indeed words can and do matter (with apologies to Donald Trump). Even though it is clear that many listeners mishear a large percentage of Dylan’s lyrics in his recordings (as indeed is the case for many pop music recordings).

There are many Dylans. Is he still equated substantially with the early protest songs?

Ira Wells: For many of his most ardent fans, Dylan has never really outgrown that phase of his career. "The Times They Are A-Changin" and "Blowin’ in the Wind": that is what Bob Dylan is. In fact, that protest period lasted only a few years. By the mid-1960s he had become something quite different. Bringing It All Back Home and Blonde on Blonde are more or less apolitical albums.

This is what is fascinating about Dylan as a cultural figure. He has changed so many times. And he has not only changed, he seems almost in a perverse way to react against the expectations and desires of his audience. Just when people are starting to celebrate him as a folk protest singer, he plugs in and becomes a rock 'n' roll star. Just when rock 'n' roll becomes culturally accepted in the late 1960s, he reinvents himself as a country song writer in Nashville Skyline. When we move into disco and punk in the late 1970s, Bob Dylan becomes a Christian gospel singer.

Is this contrarianism a literary quality?

Ira Wells: It certainly implies that he is not abiding by market imperatives. It suggests that there is something else going on. He is not responding to the marketplace as did the other well-known musical acts of his generation: The Rolling Stones, U2, Paul McCartney. Dylan rises above the marketplace. And he defies expectations in a manner that seems almost deliberately calibrated to alienate his fans. If you have ever seen him in concert, he almost never addresses the audience. He makes no attempt to entertain you. He does his thing, and you either get it or you don’t.

How will other musicians react to this?

Don McLean: Dylan was, and is, considered hugely influential by many contemporary and later musicians. I have heard this directly from Joni Mitchell and Patti Smith. The Beatles’s lyrics and generic mimicking were puerile until they started breathing at Dylan depth. These artists use song as the chariot of poetry. As with Dylan, the music bears the lyrics forward and gives them a halo of reflective complexity not always evident in the text itself.

Would it be valid to call Dylan a revolutionary?

Don McLean: The idea of “game changers” and stylistic “revolutionary steps forward” in popular music always seems improbable to classically-trained musicians, on harmonic grounds alone. But Bob Dylan’s lyrics, music and performances – "Like a Rolling Stone," "Mr. Tambourine Man," "Every Grain of Sand" – his folk-blasting electrification and his gravelly but never grovelling voice-of-God delivery have all given many cause for pause.

Does the Dylan victory give Canada hope for a Nobel? Or at least make it possible to view lyrics more critically?

Robin Elliott: Leonard Cohen would be the nearest Canadian equivalent to Bob Dylan. Both were poet-songwriters who negotiated the boundaries between folk and pop music while capturing the Zeitgeist of the 1960s and beyond. Both have received widespread acclaim and recognition for both their literary and musical activity over the past five decades and more.