‘Flying saucer’ quantum dots hold secret to brighter, better lasers, say U of T researchers

Published: March 20, 2017

More accurate medical tests, vivid video projectors and fresh insights into living cells are just three of the innovations that could result from new lasers that use nanoparticles to create brighter light in a rainbow of colours.

A new method, developed by an international research team from U of T's Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, Vanderbilt University, the Los Alamos National Laboratory and others produces continuous laser light that is less expensive, brighter and more customized than current devices by using nanoparticles known as quantum dots.

“We’ve been working with quantum dots for more than a decade,” says Ted Sargent, a professor in the department of electrical and computer engineering at U of T. “They are more than five thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair, which enables them to straddle the worlds of quantum and classical physics and gives them useful optical properties.”

“Quantum dots are well-known bright light emitters,” says Alex Voznyy, a senior research associate in Sargent’s lab. “They can absorb a lot of energy and re-emit it at a particular frequency, which makes them a particularly suitable material for lasers.”

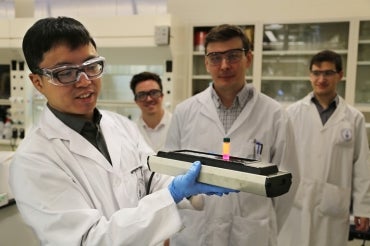

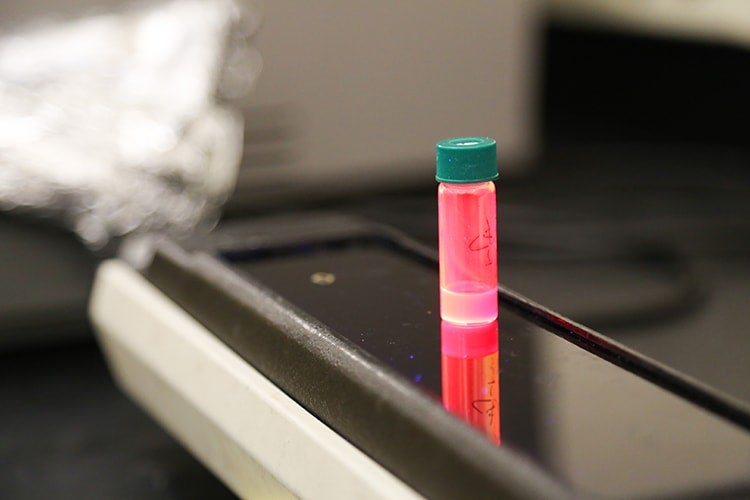

This solution of quantum dots glows bright red when in absorbs light from a UV lamp underneath. Researchers from U of T Engineering are optimizing these nanoparticles to create brighter lasers that use less energy than current models (photo by Kevin Soobrian)

By carefully controlling the size of the quantum dots, the researchers in Sargent’s lab can ‘tune’ the frequency or colour of the emitted light to any desired value. By contrast, most commercial lasers are limited to one specific frequency, or a very small range, defined by the materials they are made from.

The ability to produce a laser of any desired frequency from a single material would give a boost to scientists looking to study diseases at the level of tissues or individual cells by offering new tools to probe biochemical reactions. They could also enable laser display projectors that would be brighter and more energy efficient than current LCD technology.

But although the ability of colloidal quantum dots to produce laser light was first demonstrated by co-author Victor Klimov and his team at Los Alamos National Laboratory more than 15 years ago, commercial application has remained elusive. A key problem has been that until now, the amount of light needed to excite the quantum dots to produce laser light has been very high.

“You have to stimulate the laser using more and more power, but there are a lot of heating losses as well,” says Voznyy. “Eventually, it gets so hot that it just burns.”

Most quantum dot lasers are limited to pulses of light lasting just a few nanoseconds – billionths of a second.

The team, which included Voznyy, postdoctoral researchers Fengjia Fan and Randy Sabatini and master's student Kris Bicanic, overcame this problem by changing the shape of the quantum dots, rather than their size. They were able to create quantum dots with a spherical core and a shell shaped like a Skittle, an M&M or a flying saucer – a ‘squashed’ spherical shape known as an oblate spheroid.

The mismatch between the shape of the core and the shell introduces a tension that affects the electronic states of the quantum dot, lowering the amount of energy needed to trigger the laser. As reported in a paper published today in Nature, the innovation means that the quantum dots are no longer in danger of overheating, so the resulting laser can fire continuously.

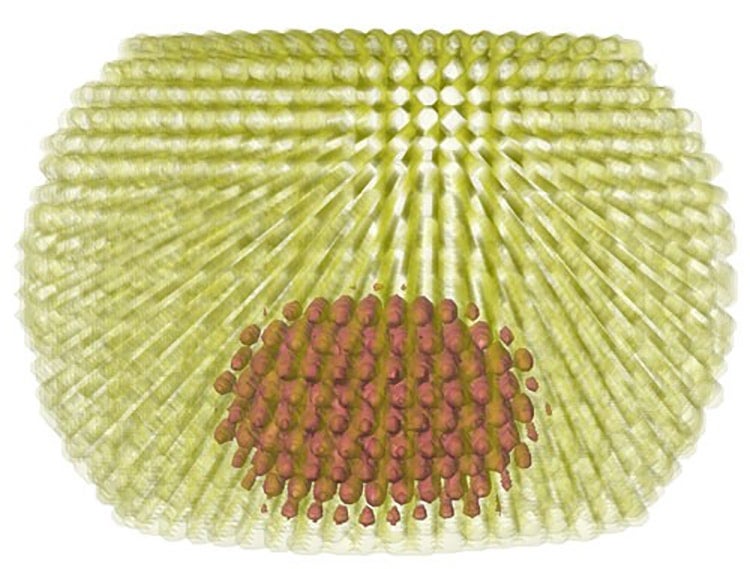

This computer-generated model shows the spherical core of the quantum dot nanoparticle (in red) along with the ‘flying saucer’ shape of the outer shell (in yellow). The tension in the core induced by the shell affects the electronic states and lowers the energy threshold required to trigger the laser (image by Alex Voznyy)

While quantum dots are often built by depositing molecules one at a time in a vacuum, Sargent’s team mixes together liquid solutions that contain various quantum dot precursors. When the solutions react, they produce solid quantum dots that stay suspended in the liquid – these are known as colloidal quantum dots. The team’s key innovation was to add specific capping molecules into the mix, which allowed them to control the shape of the particles to obtain the desired properties, an approach Fan calls ‘smart chemistry.’

“Solution-based processing greatly reduces the cost of making quantum dots,” says Fan. “It will also make it easier to scale up production because we can use techniques already established in the printing industry.”

The project included a number of national and international partners. Computer simulations in collaboration with the University of Ottawa and the National Research Council guided the design of the quantum dots. Analytical tests from Vanderbilt’s Institute of Nanoscale Science and Engineering in Nashville, TN, as well as the University of New Mexico’s Center for High Technology Materials in Albuquerque, NM and Los Alamos confirmed that the final products had the desired shape, composition and behaviour by analyzing individual quantum dots at the atomic level.

“We were impressed not only by the engineered structure itself but also by the level of uniformity they have achieved,” says Sandra Rosenthal, director of the Vanderbilt Institute for Nanoscale Science and Engineering. “Sargent’s team has managed to create quantum dots with a unique and elegant structure. This is exciting research.”

The team has more work to do before they can look to commercialization.

“For this proof-of-concept device, we’re exciting the quantum dots with light,” says Sabatini. “Ultimately, we want to move to exciting them with electricity. We also want to scale up the power to milliwatts or even watts. If we can do that, then it becomes important for laser projection.”