Desmond Morton – historian, author and former U of T principal – 'was everything a public intellectual should be'

Published: September 27, 2019

Desmond Morton was a teacher, author and rigorous academic, but also a brilliant communicator who brought history to life for the Canadian public.

Morton was a soldier and political organizer before joining the University of Toronto, where he spent 25 years of his career at Erindale College, now U of T Mississauga. His energy and enthusiasm boosted Erindale’s reputation, and as principal from 1986 to 1994 he helped expand the campus and cement ties with the community.

He died on Sept. 4 at the age of 81.

Morton brought a “sense of place” to Erindale, both as part of U of T and as an important contributor to Mississauga and the Peel region, said Ian Orchard, acting vice-president and principal of U of T Mississauga. Because of Morton, “it is in the DNA of UTM that it is a community itself, but also contributes to the broader community.”

Morton lived near the campus in Streetsville (now part of Mississauga), was engaged in local politics, and encouraged students to study local history.

While at U of T, and later at McGill University, Morton was a prolific and high-profile commentator on Canadian military, labour and political history. Over the years he wrote dozens of op-ed pieces and was interviewed often in print, radio and television.

Morton was a central player in the revitalized public interest in Canadian history that exploded in the 1980s and 1990s, said historian Paul W. Bennett, a long-time colleague and friend who is now director of Schoolhouse Consulting in Halifax. “He popularized Canadian history and did so in a way that paid respect for scholarship. He combined serious research, exquisite writing and very refined communication skills.”

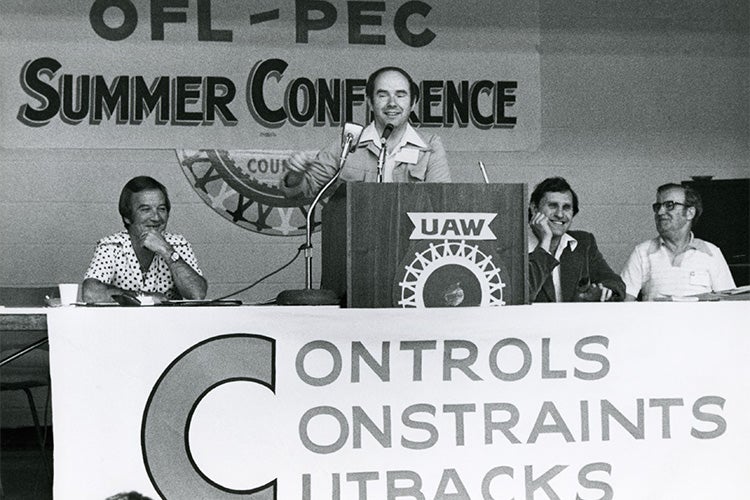

Desmond Morton speaks at an Ontario Federation of Labour conference in the late 1980s or early 1990s (photo by Steve Jaunzems)

Through a series of national history conferences, Morton brought together historians with radically different views, Bennett said. “He was a bridge builder [and] he just loved raising the level of discussion.” He was highly supportive of teaching at all levels, and was involved in presenting awards to the top history teachers across the country.

A quintessential absent-minded professor, Morton could be forgetful. He sometimes locked his keys in his car, left his glasses behind, or could be seen with his pant leg tucked into his sock. “He was a brilliant man who was so consumed by his thoughts and ideas, that the mundane and routine were not bothered with,” Bennett said.

Morton described himself as a political, military and industrial relations historian, noting that this “really adds up to the single specialty of human conflict, both violent and otherwise.” He wrote 40 books, including his seminal A Short History of Canada. First published in 1983, its seventh edition was released in 2017 and soon made it back on the bestseller lists.

Morton described himself as a political, military and industrial relations historian, noting that this “really adds up to the single specialty of human conflict, both violent and otherwise.” He wrote 40 books, including his seminal A Short History of Canada. First published in 1983, its seventh edition was released in 2017 and soon made it back on the bestseller lists.

“He had the ability to write straight-laced scholarly history with the best of them, but he also had a gift for a story and an eye for detail,” said historian Jonathan Vance, a professor of history at the University of Western Ontario. “He never forgot that history was ultimately about people.”

Morton was Vance’s external examiner for his PhD, and later became a friend and colleague. As a person, Morton “had an acerbic wit, but at heart was a kind and genial fellow,” Vance said.

Long-time colleague Robert Johnson, Professor Emeritus of history at U of T Mississauga, said Morton challenged established ideas and respectfully looked for weaknesses in people’s arguments. “He was a thoughtful, independent, contrarian voice that was profoundly important in public discourse,” Johnson said. “He was everything a public intellectual should be. He wasn’t somebody who was on a soapbox or riding a hobby horse. He asked important questions and poked holes in everybody’s dogmas.”

Desmond Dillon Paul Morton was born in 1937 in Calgary. His mother was from New Brunswick and his father, from Toronto, was an officer in the Canadian armed forces. Morton and his mother and sister moved to New Brunswick to stay with his grandparents while his father was away fighting during the Second World War.

In an autobiographical essay written in 2011 for the Canadian Historical Review, Morton said that his initial knowledge of history was gleaned from his grandfather’s Book of Knowledge encyclopedia, and faded British history books. He avoided athletic pursuits as much as possible, but learned – from a retired sea captain – how to build model wooden ships. He kept up that hobby for the rest of his life.

Former Governor General David Johnston (right) presented Morton with the Pierre Berton Award for teaching Canadian history in 2010 (photo by MCpl Dany Veillette/Rideau Hall)

After his father returned from the war, Morton and his family moved to Barrie, Ont., then to Regina. In Saskatchewan he was first exposed to political debate, when leaders such as Louis St. Laurent, C.D. Howe, Tommy Douglas, M.J. Coldwell and George Drew came to town to campaign. It was also while he was in Regina that his byline first appeared, after he wrote a letter to the CBC Times magazine. When his letter appeared in the publication, “my ego exploded,” he wrote in his memoir. “I have never quite forgotten the absurd ecstasy of seeing my name and words in print.”

In 1949 the family moved to Winnipeg, and Morton was enrolled in a private boys’ school. It was there that he started his own military career, joining the school’s cadet corps. But soon the family was off again, this time to Kingston, Ont., where Morton went to high school and joined the army reserves. His father was then transferred to Tokyo as a military attaché during the Korean War. In his summer breaks in Japan, Morton worked for a Canadian army administrative unit, and when the family returned to Canada he decided the military was where he wanted to make his career. He enrolled at College Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean, south of Montreal, then after three years continued his education and training at Royal Military College in Kingston.

Morton was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, and studied for two years at Oxford, but returned to Canada to perform his military service training officer-cadets, then moved to the army’s historical section. By this time his interest in politics had deepened, and he was persuaded by then Ontario New Democratic Party MPP Stephen Lewis to become assistant provincial secretary of the NDP. He was responsible for membership and fundraising. “I never worked harder or more happily,” he wrote. “My recreation was producing what political parties call ‘literature,’ a stream of pamphlets on issues, organization, or anything I wanted to discuss.”

After a brief stint working on a PhD at the London School of Economics, he returned to Canada, got married in 1967 to Janet Smith, and in 1970 published his thesis as his first book, Ministers and Generals, about British army officers’ attempts to command the Canadian militia.

Former Mississauga Mayor Hazel McCallion with Morton at his installation as principal in 1986 (photo by Steve Jaunzems)

In 1969 Morton accepted a job teaching history at Erindale. He thrived in the fast-growing, diverse community of Mississauga, and participated in local politics, including working on two early campaigns of long-time mayor Hazel McCallion.

“He was incredibly efficient and productive,” said Catherine Rubincam, Associate Professor Emeritus at U of T Mississauga. “He published at a ferocious rate and he taught with great energy.”

Morton was an expert at multi-tasking, Rubincam said. He would open his mail while attending long meetings, she said, but still manage to listen and participate in the proceedings.

At U of T he had the flexibility to work on a wide range of historical subjects, although his core interest was military history which he saw as “the study of people under deadly stress, making decisions and suffering from the decisions of others.”

In the early 1980s Morton was contacted by Edmonton publisher Mel Hurtig and asked to write a history of Canada that was “short enough to be bought in the Edmonton airport and finished before the buyer landed in Toronto.” Hurtig’s further instructions, Morton said, were that it had to include women, begin with First Nations and not Confederation, and not shun controversy. The result was the wildly popular A Short History of Canada. The book, as a Toronto Star reviewer said, cemented Morton’s reputation as a “first-rate storyteller” as well as a consummate historian.

Morton took on an administrative role at Erindale, as vice-principal of humanities. Then in 1986 he was named principal. He didn’t move into the opulent principal’s residence, however, as his wife Janet was confined to a wheelchair with complications from diabetes, and he wanted to stay in the house they had adapted to her needs.

Morton was an energetic and efficient administrator, said Rubincam. “He sized up situations very fast,” and then made decisions quickly.

Morton shakes hands with Ignat Kaneff as he receives an honorary degree (photo by Steve Jaunzems)

One of his major successes was the construction of the Kaneff Centre to house the social sciences faculty as well as a lecture hall and a gallery. A local donor – Ignat Kaneff, a Bulgarian immigrant who had become a successful builder in Mississauga – funded the project. Morton also spearheaded two innovative joint programs with Sheridan College.

Morton’s wife Janet died in 1990, and in 1993 he was approached by McGill University to help launch their new Institute For the Study of Canada. He decided to go, and it was in Montreal that he met his second wife Gael Eakin, whom he married in 1999.

Morton’s reputation continued to flourish at McGill, where he maintained his prolific production of textbooks, essays, newspaper articles and public appearances. He retired from teaching at McGill in 2006, but continued to write and comment on history and public affairs.

He leaves his wife Gael, children David and Marion, a granddaughter, four stepchildren and four step-grandchildren.