Canada 150: New survey finds big gaps in how we study the country's birth

Published: March 29, 2017

A recent survey of Canadian historians and political scientists, conducted by the University of Toronto and York University, has found that there are important gaps in how Canada’s 1867 Confederation is studied in this country.

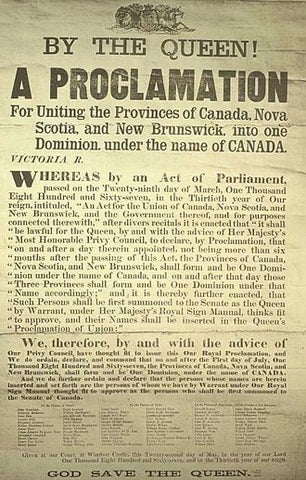

The British North America Act was passed 150 years ago today, triggering the process of Canada’s Confederation.

Canada’s 150th anniversary is heralded by some as marking a great moment in the country’s history: a view that reflects the opinion of political leaders at the time. John A. Macdonald, who went on to become Canada’s first prime minister, for example, hailed the union of British North American colonies, predicting “a great nationality, commanding the respect of the world.”

Read more at The Globe and Mail

At the same time, Canadians’ views of that landmark legislation seem to be evolving, in part because of increased awareness of the impact of the colonists on Indigenous communities.

At the same time, Canadians’ views of that landmark legislation seem to be evolving, in part because of increased awareness of the impact of the colonists on Indigenous communities.

“The survey revealed an interesting tension,” said Professor Rob Vipond of the department of political science who conducted the survey with U of T political scientist David Cameron, dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science, and colleagues at York.

“On the one hand, most respondents said they were most deeply influenced by scholars who had written in the 1960s and 1970s when the rise of Quebec nationalism led to a passionate debate about the origins of Confederation. On the other, a striking number said in effect that it was time to reframe the history of Confederation away from the national unity narrative, especially to take into account Indigenous perspectives that were largely missing from the earlier accounts.”

Among their key findings:

- Research about Confederation placed more importance on studies that focused on political elites and institutions over any other perspectives.

- Research failed to adequately address Indigenous peoples: the respondents said this needs to be included in the academic literature on 1867 going forward.

- Anglophone scholars paid limited attention to Confederation scholarship written in French whereas Francophone scholars were engaged with 1867 research whether it was written in French or English. (This finding was compatible with the determinations made by a Bilingualism and Biculturalism Commission 50 years ago that found the secondary education system has traditionally taught “two versions of Canadian history – an English version and a French version.”)

- Both Anglophone and Francophone respondents agreed that Peter Russell of U of T and the late Ramsay Cook of York University were two of the leading scholars on Confederation.

Five hundred university faculty members responded to the survey – the first detailed analysis of how universities undertake research and study of 1867. Its insights are significant not only for scholars of Confederation but for the good governance of the country.

“What scholars research and teach in universities, what we publish and share through the media, plays an important role in influencing public understanding. Many salient issues in today’s political arena are based on an understanding of what happened at the country’s establishment in 1867,” said Cameron.

In addition to U of T’s Vipond and Cameron, York University professors Lesley Jacobs, Jacqueline Krikorian and Marcel Martel conducted the survey.

Interested in learning more about the British North America Act, 1867 on its historic anniversary? Try this quiz.