From biogas to vaccines, U of T students collaborate across time zones through ‘Global Classrooms’ initiative

Published: April 13, 2022

Every Friday, four students from the University of Toronto hop on a Zoom call with students in Nigeria to share updates on their joint mission: building a low-cost biogas generator for remote communities in Africa’s most populous country.

A Global Classrooms project that brings together students in U of T’s Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering and Nigeria’s Covenant University, the international student team is using cassava peels and other agricultural waste to produce gas for cooking and heating – a more environmentally friendly and less toxic alternative to the burning of wood for fuel.

Jennifer (Chen Yu) Wang, one of the four U of T students working on the biogas generator, says the experience has been an eye-opener.

“It’s very different designing for the developed world compared to designing for a developing world context,” says Wang. “You have to approach it differently because you have a lot of constraints to work with. You might go in with a design or prototype, but there are a lot of aspects that need to be taken care of beyond the technical design.

“That’s one thing that a lot of engineers aren’t exposed to – or at least, I wasn’t. It really challenged my thinking.”

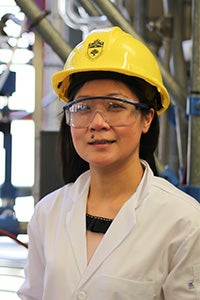

Ariel Chan

Ariel ChanThe project is the focus of a multidisciplinary capstone course that’s supervised by Ariel Chan, an assistant professor, teaching stream, and Graeme Norval, professor emeritus, teaching stream – both in the department of chemical engineering and applied chemistry. It immerses the students in a real-world engineering challenge within a Global Classrooms setting, where cross-cultural collaboration and international learning are front and centre.

“The Global Classroom enables our students to be placed in a learning environment that’s not limited to U of T – it’s in the world,” says Chan. “It helps them understand a real-life problem in a different part of the world and explore how they can use their engineering concepts to tackle it.”

Chan’s course is one of 52 U of T Global Classrooms funded by U of T’s International Office, spanning 96 partners across 34 countries and running between Summer 2021 and Summer 2022. The Global Classrooms initiative supports professors and instructors who want to provide a globally relevant educational experience to their students.

The program is currently accepting applications for the 2022-2023 cycle until May 13, with decisions on funded proposals to be made in early June. A few of the Global Classrooms were highlighted at a recent Spring Showcase, which saw instructors describe how they went about embedding international learning into their courses. They included:

- Liz Coulson, assistant professor, teaching stream, in the department of language studies at U of T Mississauga, whose students were placed in virtual classrooms in Ecuador where they taught students from kindergarten to Grade 12

- Phani Radhakrishnan, associate professor, teaching stream, in the department of management at U of T Scarborough, who co-taught a course – along with Nirusha Thavarajah, assistant professor, teaching stream, in the department of physical and environmental sciences – that saw U of T students partnering with other students around the world to design culturally relevant public health vaccination campaigns

- Phillip Lipscy, associate professor in the department of political science in the Faculty of Arts & Science and the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, whose graduate course on Canada-Japan and U.S.-Japan relations gave students the opportunity to interact with officials from Global Affairs Canada, the U.S. State Department and Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as former parliamentarians and think-tank experts

“Creating a Global Classroom requires dedication, passion and a little bit of innovation for you to understand how you can take what you’ve been teaching in the same way, for perhaps a few months or a few years, and internationalize the opportunity,” said Elham Marzi, an assistant professor, teaching stream, in the Institute for Studies in Transdisciplinary Engineering Education & Practice who also served as one of three faculty advisers for the Global Classrooms initiative in its first year.

Marzi said Global Classrooms provide students with a priceless opportunity to expand their perspectives, hone cross-cultural skills and develop compassion and empathy for people in other countries around the world and the challenges they face.

Rendering of a biogas pilot plant (image by Wilson Yeoh)

Rendering of a biogas pilot plant (image by Wilson Yeoh)“We’re hoping for every student here to be able to come away not only with global competency skills, but also with a better understanding for their fellow human,” she said.

Indeed, as Wang and her fellow U of T students go about creating simulations and designs for a generator, they’re required to adapt to resources and conditions in rural communities in Nigeria. The country-specific information is supplied by the students’ counterparts at Covenant University – Paul Oluwatosin Ojo, Isaac Oladunni, Meggison Oritsetsola and Joseph Felix Nyong – and their supervisor Professor David Olukanni.

U of T team member Truman Yuen says Global Classrooms creates real-world challenges that are difficult to replicate “even in internships,” given the variability of standards and protocols in countries around the world.

“When we’re creating a design that is unprecedented and new in a developing country, there are so many other things to consider that we don’t think about,” Yuen says. “So, this is a nice experience which, when we tackle future designs, will help us appreciate how the standards and roles that are put in place for us here help with our design process.”

The project also helped students hone a variety of soft skills, according to Jenny Pham, whose duties included serving as the point of communication between the two teams of students and their professors.

“We had to co-ordinate different timelines and deadlines, making sure that we’re able to communicate our points or discuss deliverables with the other team,” said Pham. “Working with people on the other side of the globe in such a big team really improved those soft skills for us.”

Wilson (Wei Cheng) Yeoh, the only U of T mechanical engineering student in the group (the other three are studying chemical engineering) noted the importance of developing a rapport with the students in Nigeria.

“At the beginning of the project, we had to spend time not just talking about the technical aspects but also about ourselves and our expectations,” he said. “The cultures and norms that apply to our university context might not be the same for the other university. That’s one thing I learned the most.”

For Yeoh, an international student from Malaysia, the project was also an opportunity to develop skills that might be helpful back home where, he notes, vast amounts of agricultural waste are generated each year.

“If I have the chance, I’d love to take what I’ve learned collaborating with Nigeria and apply it in Malaysia,” he says.

The students weren’t the only ones to find the Global Classroom a fulfilling learning experience.

“It pushed me to consider a lot of possibilities in engineering design and allowed me to see how design can be flexible and how a variety of combinations can be used to achieve the same result,” said Chan, their professor.

“But also, [it taught me] compassion and helped me see how I can be of use beyond just teaching – by contributing as a global citizen.”