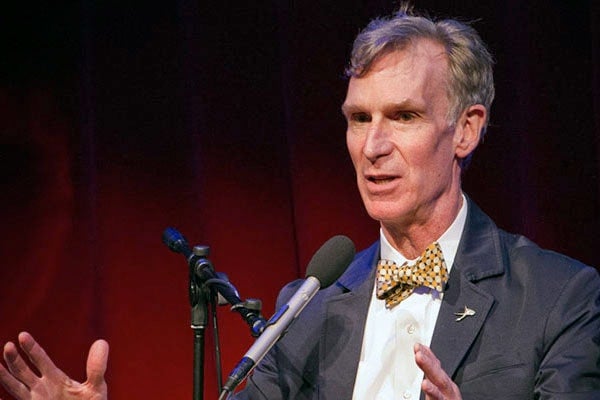

Bill Nye on science literacy and his upcoming visit to U of T

Published: September 26, 2014

For many kids who grew up in the 90s, one of the joys of science class was seeing a TV trolley wheeled in, with an episode of Bill Nye the Science Guy ready to go.

Since then, Bill Nye’s impact on science education has grown beyond the walls of science class.

The scientist, comedian, writer, television personality and former engineer now engages the public in the wonders of science through The Planetary Society, the world’s largest space interest group.

On October 1, The Planetary Society, along with Nye and special guests, will be at Convocation Hall to discuss and celebrate Canada’s space program as part of the International Astronautical Congress.

The event comes on the heels of Science Literacy Week (September 22-28). Spearheaded by alumnus Jesse Hildebrand and U of T Libraries – and in collaboration with the Toronto Public Library and York University – Science Literacy Week is a city-wide event that offers public access to documentary screenings, book displays and lectures, among other offerings, to showcase the field of science in its many forms.

Writer Liz Do spoke to Nye about the importance of science literacy, as well as the upcoming event at Convocation Hall.

What contributions have Canadians made to space science?

I remind Canadians that they should be very proud of their space agency. The Canadian Space Agency manages to get itself on so many space missions and Canada provides so much ground support for so many people around the world.

Canadians are involved in developing a lot of space instruments: there’s a Canadian instrument on the Curiosity Rover, and there’s a Canadian instrument on Maven, which got captured in Mars’ orbit recently. Canada also participated on Hayabusa [an unmanned spacecraft], which went past Venus. There are also a great number of communication and weather satellites that the Canadian Space Agency is involved in.

And, who doesn’t love Chris Hadfield? When you put humans in space, you really engage people.

It’s Science Literacy Week here at U of T. Who or what got you fascinated by science?

I do remember, very well, being fascinated by bees. I sat and watched bumblebees for days. They’d fly and hover and fly back to fill up their pollen baskets from azalea flowers, and then go flying off again and come back… I got to a point where I was convinced I was seeing the same bee coming and going from the flowers.

When I got stung by a bee, my mom put ammonia on it, and then my brother, who had a chemistry kit, made ammonia. I remember thinking, ‘That’s the coolest thing. There’s some amazing connection between chemistry and the universe.’ My grandfather was also an organic chemist, and my mom gave me his glassware to play with.

When it came time to make choices, like when you’re in first grade and the teacher asks you ‘do you want to do science or do you want to colour?’ I would want to do the science thing. I remember [my teacher] teaching us about Oases – when water can flow underground – and I thought that that was amazing!

If I put that question to science students here, they might tell me that Bill Nye the Science Guy had something to do with their interest.

That’s pretty cool. That’s the goal!

As Bill Nye the Science Guy you made science so accessible and exciting. What influenced the approach to the show?

Well any television show, and this is lost on some people, has to be entertaining first. A lot of people take what they do very seriously, and they figure it’s just up to the audience to be entertained. But making things funny is hard, or it can be hard. You can pretend to be serious, but you cannot pretend to be funny.

And teaching, in my opinion, is a performing art. That may be obvious, but not to everybody.

Science Literacy Week includes virtual exhibits featuring recommended books, podcasts and videos. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading a book that’s coming out soon called, The Moral Arc of Science by Michael Shermer. He argues that science is what makes us more civilized; it’s very cool.

And my book is coming out in November, it’s called Undeniable: Evolution and The Science of Creation. I would call it a primer on evolution – natural selection, sexual selection, homology. I also talk at length about that debate in Kentucky.

How important is science literacy?

When it’s time to vote, when it’s time to influence policy, we need voters who can think critically and understand the reasonableness of scientific arguments.

It’s more important than it’s ever been in my lifetime, that’s for sure.

In the last year, both Neil deGrasse Tyson and Chris Hadfield visited U of T to give lectures to our students, and both events were sold out within hours. They’ve become science figureheads in pop culture, thanks to their ability to engage with the public through television and social media. Do you think this fascination with science is going to stay or grow in pop culture?

I’m working hard to make it grow through my work with the Planetary Society – where Neil is a board member, by the way. We work as hard as we can to promote science literacy, because for me, it’s in the best interest for all of humankind.

Yet scepticism of science is quite pervasive today, whether it’s denying climate change, or evolution. Is it frustrating to have to publicly shoulder much of this debate? Is there value in having this debate?

We want as many people to be aware of [climate change] as possible, and be aware of the debate. I think that, a century from now, there will be a lot less of this – denial of climate change, denial of evolution.

But you’ve got to work with what you’ve got, both where and when you were born. I’m living in a time where we have these fantastically difficult problems to solve around the world – climate change being the most serious – and we have a bunch of people who are voters who don’t believe that it’s an important problem. And some people are using an old trick where you take scientific uncertainty, and convert that into your listener’s mind to doubt the whole thing.

The problem is, we have seven billion people, and the atmosphere is barely the thickness of a layer of varnish on a classroom globe – all these people trying to breathe and burn the same atmosphere.

But you have to be optimistic. You have to go into it like we’re going to solve this.

Last question – simply put, why should we get excited about science?

It’s the best idea humans have ever had. It’s how we know nature and our place in the universe. Science is what brings us all the technology and food that we rely on for our extraordinary quality of life. Without science, no one would live nearly as well as he or she does right now.